Documentos

Mala Budista

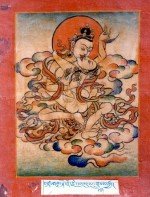

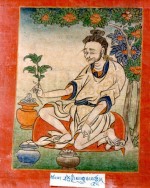

“…mantras for ”Increasing” should be recited using malas of Bodhi seeds, gold or amber. The mantras counted on these can “serve to increase the fortune of life” such like mantra of Yellow Jambhala.(the god of wealth)…”

Dzi Bead – Coral – Âmbar

A mala is a set of beads used for counting “mantras” which are the expression of a Buddha-aspect on the level of sound. The number of mantras gets counted to ensure certain meditation results will occur.

In Tibetan Buddhism, traditionally malas of 108 beads are used. Doing one 108-bead mala counts as 100 mantra recitations; the extra repetitions are done to amend any mistakes. The materials used to make the beads can be different according to the purpose of the mantras beening used. These beads can be made from Bodhi seeds, Rudraksha seeds, lotus seeds( called ‘Moon and Stars’ by Tibetan) , sandalwood, abelia, gold, silver, copper, iron, crystal, coral, ivory, amber, coloured glaze, turquoise, giant clam, pearls and so forth, and even bones of a holy monk or revered lama.

Holy bone malas are made from the bones of mahasiddhas or lamas and hand made by highly skilled lamas, therefore, they are extremely precious. The lama who makes the holy bone mala, will chant mantras while shaping the bones into beads and polishing them. The whole process of making a holy bone mala may take over one decade, hence there goes a saying in Buddhism: holy bone malas can bring peace to the dead and safety to the living. What the holy bone mala represents, in mundane words, is that life is ever-changing and death may knock at your doors in anytime, therefore, one should be diligent in his or her practice; in Dharmata chos nyid, is the emptiness.

Cristal de Quartzo

Some beads, such as the ones made of lotus seeds, can be used for all purposes and all kinds of mantras. However, in Tibetan Buddhism, beads are recited for four different purposes:

1: Pacifying mantras should be recited using white colored malas such as crystal. These can serve to purify mind and clear away obstacles in one’s life, like illness, bad karma and mental disturbances.

2: Increasing mantras should be recited using malas of Bodhi seeds, gold or amber. The mantras counted on these kinds of mantras, for instance, mantra of Yellow Jambhala, can “serve to increase life span, knowledge and merits”.

2: Increasing mantras should be recited using malas of Bodhi seeds, gold or amber. The mantras counted on these kinds of mantras, for instance, mantra of Yellow Jambhala, can “serve to increase life span, knowledge and merits”.

3: Mantras for magnetizing are meant to tame others, but the motivation for doing so should be a pure wish to  help other sentient beings and not to benefit oneself. To do mantra of Amitayus and Kurukulle, malas made of coral should be used.

help other sentient beings and not to benefit oneself. To do mantra of Amitayus and Kurukulle, malas made of coral should be used.

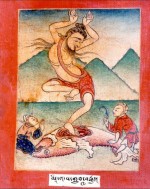

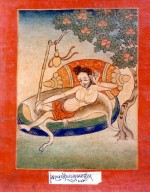

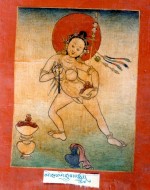

4: Mantras to tame by force should be recited using malas made of bones of mahasiddhas. Reciting this kind of mantras with mala serves to tame others, but with the motivation to unselfishly help other sentient beings. To tame by force means to subdue harmful energies, such as “extremely malicious spirits, or general afflictions”. Only a person such like Dakini  that is motivated by great compassion for all beings, including those they try to tame, can do this.

that is motivated by great compassion for all beings, including those they try to tame, can do this.

Beads made of lotus seeds can be used for many purposes and for counting all kinds of mantras.

Que todos possam se beneficiar!

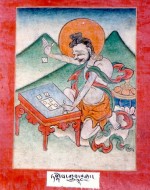

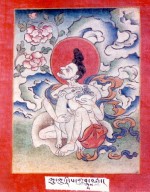

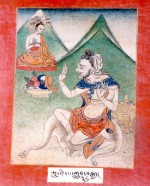

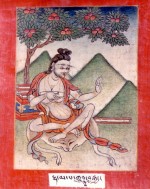

84 Mahasiddhas

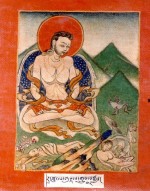

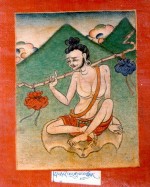

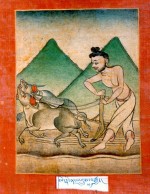

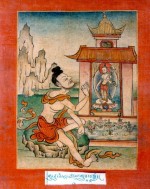

Mahasiddhas – Who Has Attained Highest Level Accomplishment

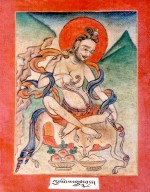

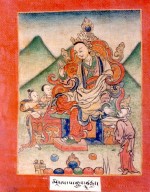

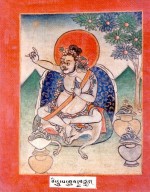

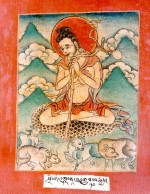

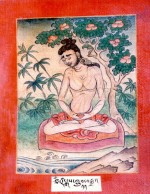

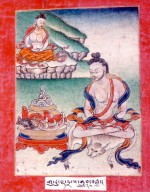

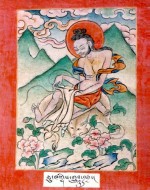

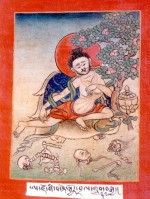

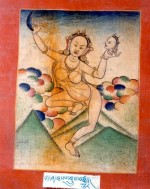

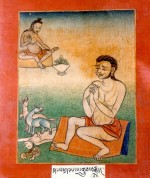

The Mahasiddhas, literally the ‘Greatly Attained Ones’, lived in India between the 8th and 12th centuries and were the instigators of the highly esoteric Yoga Tantra systems that were finally transmitted into Tibet. The Mahasiddhas came from all walks of life, and the diversity of their often-outlandish legends reveals much about the different approaches to enlightenment.

A practitioner who has attained the high level of realization of an Arhat is said to acquire at least six siddhis or powers. These powers include such seemingly miraculous abilities as the power to fly, to levitate, to make oneself invisible, to possess another person’s body, to decrease or increase one’s size at will, and to assume other forms at will. There are said to be 84 siddhis that one can attain through the ultimate realization of emptiness and the attainment of enlightenment. These 84 siddhis are exemplified in the popular stories of the 84 Mahasiddhas, each of whom represents one of the siddhis. These stories are very popular and well-known throughout Tibet and India as well as the other Buddhist countries of Asia.

One thing that stands out when reading the stories of the 84 Mahasiddhas is how different each of them are from the others. Some were kings, some monks, some itinerant ascetics, some fishermen and butchers. The one common thread throughout all the stories, however, is that these individuals all broke free of the limits and boundaries imposed on them by their circumstances and livelihoods. Monks, kings, householders, having accomplished the subtle practices of the highest tantric yogas, all abandoned their robes or their crowns or their families and wandered the mountains and charnel grounds free of attachment to anyone or anything. They often appeared as crazy hermits, unbound by any rules and living seemingly as they chose. Yet all remained true to their realization and their wish to liberate all beings from suffering.

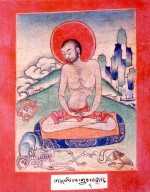

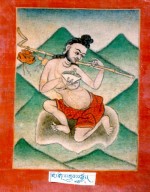

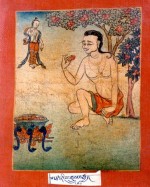

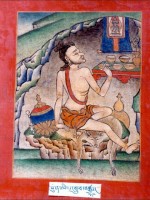

- Mahasiddha Luyipa Lūyipa / Luipa (nya’i rgyu ma za ba): “The Eater of Fish Intestines” ”The Fish-Gut Eater”

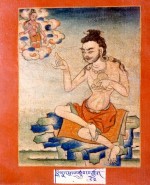

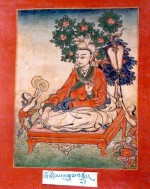

- Mahasiddha Lilapa Līlapa / Līlāpāda (sgeg pa): “He Who Loved the Dance of Life” ”The Royal Hedonist”

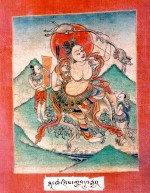

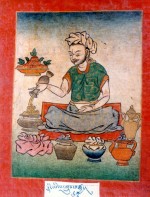

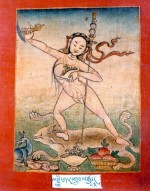

- Mahasiddha Virupa… Virūpa / Dharmapala (bi ru pa): “The Wicked” ”Master of Dakinis”

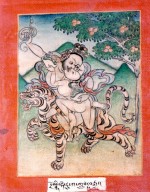

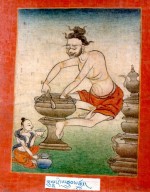

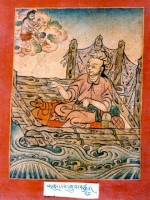

- Mahasiddha Dombhipa Dombipa / Dombipāda (dom bhi he ru ka): “He of the Washer Folk” ”The Tiger Rider”

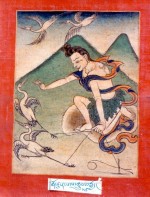

- Mahasiddha Shawaripa Savaripa / Shavaripa / Sabaripāda (ri khrod dbang phyug): “The Peacock Wing Wearer” ”The Hunter”

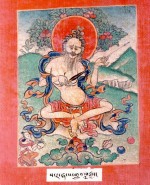

- Mahasiddha Saraha: The “Arrow Shooter”]”The Great Brahmin”

- Mahasiddha Kangkalipa Kankaripa / Kankālipāda (kanka ri pa): “The One Holding the Corpse” ”The Lovelorn Widower”

- Mahasiddha Menapa Mīnapa / Vajrapāda / Acinta (nya bo pa): “The One Swallowed by a Fish” ”The Avaricious Hermit” ”The Bengali Jonah”

- Mahasiddha Goraksa Goraksa (ba glang rdzi): “The Immortal Cowherd”

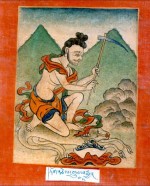

- Mahasiddha Sorangipa Courangipa: “The Limbless One”

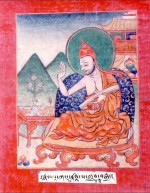

- Mahasiddha Vinapa Vīnapa / Vīnapāda (pi vang pa): “The Lute Player” ”The Music Lover”

- Mahasiddha Santipa Sāntipa / Ratnākarasānti (a kar chin ta): “The Academic”

- Mahasiddha Tantipa Tantipa / Tantipāda (thags mkhan): “The Weaver” ”The Senile Weaver”

- Mahasiddha Tsamarepa Camaripa / Tsamaripa (lham mkhan): “The Leather-worker” ”The Divine Cobbler”

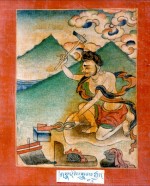

- Mahasiddha Khadgapa Khadgapa / Pargapa / Sadgapa (ral gri pa): “The Swordsman” ”The Master Thief”

- Mahasiddha Nagarjuna: “Philosopher and Alchemist”

- Mahasiddha Khanapa Kānhapa / Krsnācharya (nag po pa): “The Dark Master” ”The Dark-Skinned One”

- Mahasiddha Karnarepa Karnaripa / Āryadeva (‘phags pa lha): “The One-Eyed” ”The Lotus Born”

- Mahasiddha Thaganapa Thaganapa / Thagapa (rtag tu rdzun smra ba): “He Who Always Lies” ”Master of the Lie”

- Mahasiddha Naropa/Narotapa Naropa / Nādapāda (rtsa bshad pa): “He Who Was Killed by Pain” ”The Dauntless Disciple”

- Mahasiddha Shalipa Shalipa / Syalipa (spyan ki pa): “The Jackal Yogin”

- Mahasiddha Tilopa Tilopa / Prabhāsvara (snum pa / til bsrungs zhabs): “The Sesame Grinder” ”The Great Renunciate”

- Mahasiddha Saktrapa Catrapa / Chatrapāda (tsa tra pa): “The Beggar Who Carries the Book”

- Mahasiddha Bhadrapa Bhadrapa / Bhadrapāda (bzang po): “The Auspicious One” ”The Snob”

- Mahasiddha Dukhandhipa Khandipa / Dukhandi (gnyis gcig tu byed pa / rdo kha do): “He Who Makes Two into One”

- Mahasiddha Ajokipa Ajokipa / Āyogipāda (le lo can): “He Who Does Not Make Effort”

- Mahasiddha Kalapa Kalapa / Kadapāda (smyon pa): “The Madman” ”The Handsome Madman”

- Mahasiddha Dhubipa Dombipa / Dombipāda (dom bhi he ru ka): “He of the Washer Folk” ”The Tiger Rider”

- Mahasiddha Kankana Kankana / Kikipa (gdu bu can): “The Bracelet Wearer”

- Mahasiddha Kambala Kambala / Khambala (ba wa pa / lva ba pa): “The Yogin of the Black Blanket”

- Mahasiddha Bhendepa Bhandhepa / Bade / Batalipa (nor la ‘dzin pa): “He Who Holds the God of Weath”

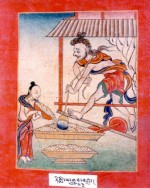

- Mahasiddha Dhingipa Tengipa / Tinkapa (‘bras rdung ba): “The Rice Thresher”

- Mahasiddha Tantepa Tandhepa / Tandhi (cho lo pa): “The Dice Player” ”The Gambler”

- Mahasiddha Kukuripa Kukkuripa (ku ku ri pa): “The Dog Lover”

- Mahasiddha Kuzepa Kucipa / Kujiba (ltag lba can): “The Man with a Neck Tumor”

- Mahasiddha Dhamapa Dharmapa – (tos pa can): “The Man of Dharma”

- Mahasiddha Mahalapa Mahipa / Makipa (ngar rgyal can): “The Braggart”

- Mahasiddha Acinta Acinta / Atsinta (bsam mi khyab pa / dran med pa): “He Who is Beyond Thought”

- Mahasiddha Babehepa Babhahi / Bapabhati (ch las ‘o mo len): “The Man Who Gets Milk from Water”

- asiddha Shantideva Bhusuku / Shantideva (zhi lha / sa’i snying po): ”The Lazy Monk”

- Mahasiddha Indrabuti Indrabhūti / Indrabodhi (dbang po’i blo): “He Whose Majesty Is Like Indra” ”The Enlightened King”

- Mahasiddha Mekopa Mekopa / Meghapāda (me go pa): “The Wild-Eyed Guru”

- Mahasiddha Toktsepa Kotali / Kotalipa / Togcepa (tog rtse pa / stae re ‘dzin): “The Ploughman” ”The Peasant Guru”

- Mahasiddha Kamparipa Kamparipa / Kamari (ngar pa): “The Blacksmith”

- Mahasiddha Zaledarapa Jālandhari / Dzalandara (dra ba ‘dzin pa): “The Man Who Holds a Net” ”The Chosen One”

- Mahasiddha Rahulagupta Rāhula (sgra gcan ‘dzin): “He Who Has Grasped Rahu”

- Mahasiddha Dharmapa Dharmapa (thos pa’i shes rab bya ba): “The Man of Dharma”

- Mahasiddha Dhokaripa Dhokaripa / Tukkari (rdo ka ri): “The Man Who Carries a Pot”

- Mahasiddha Medhenapa Medhina / Medhini (thang lo pa): “The Man of the Field”

- Mahasiddha Sankazapa Pankaja / Sankaja (‘dam skyes): “The Lotus-Born Brahmin”

- Mahasiddha Gandrapa Ghandhapa / Vajraganta / Ghantapa (rdo rje dril bu pa): “The Man with the Bell and Dorje” ”The Celibate Monk”

- Mahasiddha Zoghipa Yogipa / Jogipa (dzo gi pa): “The Candali Pilgrim

- Mahasiddha Tsalukipa Caluki/Culiki: “The Revitalized Drone”

- Mahasiddha Gorurapa Godhuripa / Gorura / Vajura (bya ba): “The Bird Man” ”The Bird Catcher”

- Mahasiddha Lutsekapa Lucika / Luncaka (lu tsi ka pa): “The Man Who Stood Up After Sitting”

- Mahasiddha Nalinapa Nalina / Nili / Nali (pad ma’i rtsa ba): “The Lotus-Root”

- Mahasiddha Nigunapa Niguna / Nirgunapa (yon tan med pa): “The Man without Qualities” ”The Enlightened Moron

- Mahasiddha Nandhipa Jayananda: “The Crow Master”

- Mahasiddha Patsaripa Pacari / Pacaripa (‘khur ba ‘tsong ba): “The Pastry-Seller”

- Mahasiddha Tsampakapa Campaka / Tsampala (tsam pa ka): “The Flower King”

- Mahasiddha Bhichanapa Bhiksanapa / Bhekhepa (so gnyis pa): “The Man with Two-Teeth” ”Siddha Two-Teeth

- Mahasiddha Dhelipa Telopa / Dhilipa (mar nag ‘tshong mkhan): “The Seller of Black Butter” ”The Epicure”

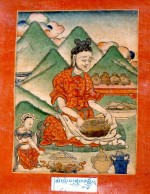

- Mahasiddha Kumbharipa Kamparipa/Kamari: “The Potter”

- Mahasiddha Sarwatripa Caparipa

- Mahasiddha Manibhadra: “She of the Broken Pot” ”The Model Wife”

- Mahasiddha Mekhala: “The Elder Severed-Headed Sister”

- Mahasiddha Kanakhala: “The Younger Severed-Headed Sister”

- Mahasiddha Kalakala Kilakipala: “The Exiled Loud-Mouth”

- Mahasiddha Kantalipa Kantali: “The Tailor” ”The Rag Picker”

- Mahasiddha Dhahulipa Dhahuli / Dekara (rtsva thag can):“The Man of the Grass Rope”

- Mahasiddha Kapalapa Kaphalapa / Kapalipa (thod pa can): “The Skull Bearer”

- Mahasiddha Udhelipa Udhilipa: “The Flying Siddha”

- Mahasiddha Kiralawapa Kirava/Kilapa (rnam rtog spang ba): “He Who Abandons Conceptions” ”The Repentant Conqueror”

- Mahasiddha Sakarapa Saroruha / Sakara / Pukara / Padmavajra (mtsho skyes): “The Lake-Born” ”The Lotus Child”

- Mahasiddha Sarwabaksa… Sarvabhaksa (thams cad za ba): “He Who Eats Everything”/”The Empty Bellied Siddha”

- Mahasiddha Nagabhodhi Nāgabodhi (klu’i byang chub): “The Red Horned Thief

- Mahasiddha Dharikapa Dārika / Darikapa (smad ‘tshong can): “Slave-King of the Temple Whore”

- Mahasiddha Putalipa

- Mahasiddha Sahanapa Panaha

- Mahasiddha Kokilapa Kokalipa / Kokilipa / Kokali (ko la la’i skad du chags): “The One Distracted by a Cuckoo”

- Mahasiddha Anangapa Ananga / Anangapa (ana ngi):“The Handsome Fool”

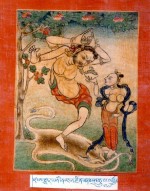

- Mahasiddha Lakshimikara Laksminkara: “She Who Makes Fortune” ”The Mad Princess”

- Mahasiddha Samudra: “The Beach-comber”

- Mahasiddha Vyalipa: “The Courtesan’s Alchemist”

This document is free for download and personal use. They are not to be published commercially. All rights reserved.

Dharma terms collection

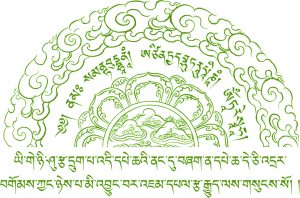

DEDICATION

To the long life of the infinitely kind and precious teachers, loving guides, Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche, and Khenpo Tulku Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche; to the Buddha’s Teachings, the Unsurpassable Dharma, the Clear-Light of Spiritual Intelligence, the Great Perfection of Wisdom. These pages have been gathered, edited, pinched and pasted by the slothful and, bumbling dharma child, Pema Kundal Da’ser, further complicated by the random offerings and eccentricities of the archaic upasaka Drakpakarpo, now an ongoing project freely shared with the sangha, loving friends, precious companions and anyone else out there who happens to click in… may this be of benefit to all, may the maha-siddhi pervade the realm of sentient life, may positive potential go forth through each one of us, unto all sentient beings everywhere.

This document is free for download and personal use. They are not to be published commercially. All rights reserved.

A

Abhidharma (S): Tibetan: Chö-ngön-pa. One of the three baskets (tripitaka) of the Buddhist canon, the others being the Vinaya and the Sutra; the systematized philosophical and psychological analysis of existence that is the basis of the Buddhist systems of tenets and mind training. The scholastic system of metaphysics that originated in Buddha’s discourses regarding mental states and phenomena. Originally taking form at the first Buddhist Council, the final modifications took place between 400 and 450 ce.

abhisheka (S): Tibetan: wang. See: Empowerment.

accumulation of merit: Sanskrit: punysambhãra; Tibetan: sonam shok. Accomplishment of virtuous activities accompanied by correct motivation, which is a “reserve of energy” for spiritual evolution. This accumulation is done by very varied means: gifts, offerings, recitation of mantras and prayers, visualizations of divinities, constructions of temples or stupas, prostrations, circumambulations, appreciation of the accomplishments of others, etc. One of the “two accumulations,” necessary for enlightenment, the other being the accumulation of wisdom.

accumulation of wisdom: Sanskrit: jñãnasambhãra; Tibetan: yeshe shok. Development of knowledge of the nature of the emptiness of all things; obtained by contemplating the profound truth of emptiness. One of the “two accumulations,” the other being the accumulation of merit.

acharya (S): Teacher or spiritual guide. An honorific title denoting great spiritual attainment.

action seal: Sanskrit: karma-mudra. Tibetan: le kyi chag gya. A tantric consort in the sexual practices of highest tantric yoga.

action tantra: Kriya Tantra. First of the four classes of tantra. It emphasizes external ritual, purity in behavior, vegetarianism and cleanliness. The meditation deity is separate and other than onself. See Dzogchen; Atiyoga

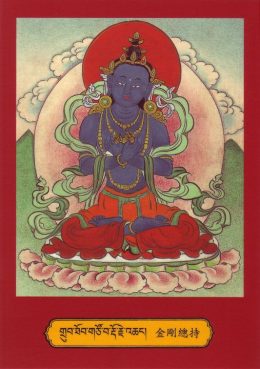

Adibuddha (S): The original Buddha, eternal with no beginning and with no end. In Mahayana Buddhism, the idea evolved, probably inspired by the monotheism of Islam, that ultimately there is only one absolute power that creates itself. He is infinite, self-created and originally revealed himself in the form of a blue flame coming out of a lotus. Over time this symbol was also personified in the form of the Adibuddha. There are various forms and manifestations in which this supreme essence of Buddhahood becomes manifest.

advaita (S): Nondual; not two. Nonduality or monism. The Hindu philosophical doctrine that Ultimate Reality consists of one principle substance, Absolute Being or God. Opposite of dvaita, dualism. Advaita is the primary philosophical stance of the Vedic Upanishads, and of Hinduism, interpreted differently by the many rishis, gurus, panditas and philosophers. See: Vedanta.

affliction: Sanskrit: klesha; Tibetan: nyon mong. Any emotion or conception that disturbs and distorts consciousness. The six root afflictions are attachment, anger, self-importance, ignorance, wrong views and emotional doubt.

aggregates: Sanskrit: skandha. Tibetan: phung po. The components of the psycho-social personality by which beings impute the false notion of self; the five components of the individual existence:

1. Form (matter): (S. rupa, T. zug) The physical body, mind and of sense organs. The body is thus analyzed in terms of the five elements: space, solidity, fluidity, motion, and heat.

2. Sensation: (S. vedana, T. tsor wa) Analyzed in terms of the sense organs, feelings are of three distinct kinds: pleasant, unpleasant or neutral. The mind is considered a sense organ.

3. Perception: The relationship between outer forms presented by the five sense organs and the inner mind through the process of naming and categorization; the interaction between mind, sense organs and their objects gives rise to feelings which are further qualified by perception.

4. Mental Formation: This includes all of the willed actions of the mind. This is the skandha associated with volition and the formation of new karmas.

5. Consciousness: (S. vijnana, T. nam par she pa)The resultant moment of conditional awareness which arises when suitable conditions conspire. When the mind makes contact with an object simple read-out awareness arises as a result of the contact. The Buddha taught that consciousness does not arise without conditions. These conditions are brought into the present through the mechanism of the first four skandhas.

agura (S): Sitting cross-legged, where neither foot is placed firmly on the opposite thigh. This is neither the half or full lotus position. It is the common cross-legged position used to sit on the floor in the West.

AH (S): Mantra seed syllable (bija) symbolizing great emptiness from which all forms arise, the speech of all the buddhas, or the “Vajra Speech of the Buddhas.” Associated with the Sambhogakaya (Beatific Body or Body of Bliss, Rapture, Perfect Enjoyment), the color ruby and the throat chakra.

ahamkara (S): “I-maker.” Personal ego. The mental faculty of individuation; sense of duality and separateness from others. Sense of I-ness, “me” and “mine.” Ahamkara is characterized by the sense of I-ness (abhimana), sense of mine-ness, identifying with the body (madiyam), planning for one’s own happiness (mamasukha), brooding over sorrow (mamaduhkha), and possessiveness (mama idam). See anava mala, ego

ahimsa (S): Harmlessness. Action that is non-injuring; non-violence.

Ajatasatru (S): Tibetan: Ma-kye-dra. Ajatasatrua was Prince of Magadha who plotted with Buddha’s manipulative cousin Devadatta, imprisoned and killed his father, King Bimbisara. Realizing the enormity of his sin he sought refuge in the Buddha, he made efforts to purify this negativity and some believe he became an arhat. King Ajatasatru sponsored the first Buddhist council. King Bimbisara of Magadha was imprisoned by his ambitious son and either starved to death or committed suicide. Ajatasatru ascended to the throne and expanded his territory by conquests. Ajatasatru also waged war with King Prasenajit of Kosala but was defeated. He married Prasenajit’s daughter. Ajatasatru patiently schemed for 16 years to break the unity and strength of Vajjis. He quarreled with this strong confederacy led by Cetaka for reasons which are differently given by Buddhists and Jains. However it was not easy to break the solidarity of the Licchavis and other members of the confederacy. Ajatasatru resorted to foul methods, sowing seeds of discord among different classes of the confederacy through one of his ministers who settled amongst the Vajjis and became adept in destroying the social unity of the people. Ajatasatru eventually executed King Cetaka, (Mahavira’s uncle) and took over the area which had been held by the Vajji confederacy.

Akashagarba (S): Tibetan: Namkhai Nyingpo, “Matrix of the Sky.” Akashagarba is the principle Bodhisattva of the Jewel Family. He is associated with the Eastern wisdom through the dawning of light from that direction. He wears a white robe and holds a lotus with a large sword shedding that light in his left hand. He is known for his generosity and meritorious acts.

Akshobhya (S): Tibetan: Mi-kyö-pa. “Unshakeable One.” Lord of the Vajra Family, one of the five dhyani buddhas, or heads of the five buddha families, representing the fully purified skandha, or aggregates of form. In the Natural Liberation, he represents the wisdom-mirror and the transmutation of the poison of aggression and hatred. Akshobhya is blue, and is associated with the east and the ground – Abhirati Buddha. He originates from the blue seed syllable HUM and represents the vajra family; immutable and imperturbable. The path to enlightenment through the Vajra family is one of breaking free of constraints and obstacles, transmuting negativity, and is generally more dynamic and proactive. He makes the earth touching mudra (S. bhumisparsa) with the tip of the middle finger touching the earth with palm drawn inwardly, while his left hand rests on his lap face . He faces the East and, is often depicted with his consort Lochana, She of the Buddha Eye, who expresses the mirror-like primordial wisdom.

alaya (S): Abbreviation of Alaya-vijanana. A division of the mind into eight consciousness was introduced by the Yogacara schools. Alaya is considered the eighth, a sort of ground or eternal matrix, a storehouse of creativity containing all karmic traces and phenomenal possibilities; ultimately, it is transpersonal and is the receptacle or totality of consciousness both absolute and relative. In the Yogacara school it is described as the fundamental mind or ground consciousness of sentient beings, which underlies the experience of individual life, and which stores the germs of all future affairs. It is the eighth consciousness which transforms into Mirror-like wisdom.

Amdo (T): Region of northeastern Tibet. Today, it includes the bulk of Qinghai Province as well as the Kanlho Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Gansu Province. Along with Kham and U-Tsang, it is one of Tibet’s three historic regions. Each of these regions speaks its own distinctive dialect of Tibetan. Amdo is also known in Tibetan as Dotoh province.

Amitabha (S): Tibetan: Opame. “Boundless Light.” The Buddha of Limitless Light, Lord of the Lotus Family (Padma); one of the Five Dhyani Buddhas, the fourth and most ancient of the five Transcendental Buddhas that embody the five primordial wisdoms. He presides over the Western Buddha realm Sukhavati (Tibetan: Dewachen, “Pure Ground of Great Bliss”), which is the expression of his own field of compassionate wishes, pure heart and nothing else. Having manifest a place of awakening accessible to all beings, it is the special vow of Amitabha that in order to benefit beings who are caught in the realm of their own confusion and suffering, one must only remember his name with faith at the time of their death to take rebirth in Dewachen. Through this birth they will easily achieve enlightenment and not again fall into a realm of suffering. This is due to the merit-power of Buddha Amitaba’s virtuous activities accumulated throughout countless lives as a bodhisattva.

Amitabha is the pure expression of the wisdom of discriminating awareness, which transmutes the poison of attachment and desire. He and the other Lotus family members support the gradual unfolding of one’s spiritual petals into enlightenment. The embodiment of compassion and wisdom, he is depicted as sitting in the lotus posture upon a great lotus blossom throne (symbolizing primordial purity), his body radiating the color of the ruby and clothed in monastic attire. His hands are in the Meditation Mudra, (the right hand rests on the left hand above the lap with the tips of the thumbs touching), and holding an alms bowl. Embodying the Wisdom of Discriminating Vision, he transmutes mundane perception into inner vision. In some mandalas, Amitabha is depicted in union with his Wisdom Consort Gokarmo, who embodies the pure element of fire. The eminent bodhisattva Avalokitesvara (Chenrezig) the Bodhisattva of Compassion is an emanation of Amitabha.

In China, Amitabha and his Buddha land are described in the Smaller Pure Land Sutra and the Greater Sukhavati Sutra. A third Sutra was written in China, entitled the Visualizations of the Buddha of Infinite Life Sutra. This pertains to another reflex of Amitabha known as Amitayus. These Sutras, as well as others such as the Aksobhya Buddha Sutra, served as the central scriptures for a populist practice intended for lay Indian Buddhists incapable or uninterested in delving into the intricate philosophies and meditations of monastic Buddhism. Although there is no evidence that they were the center of any organized sect of Indian Buddhism, when these Sutras were translated into Chinese, a cult soon developed around them which would blossom during the Tang dynasty (618-907 AD) into a full fledged sect of Chinese Buddhism, called the Pure Land. This sect has continued to influence Chinese Buddhism to this day, as it has been absorbed into the Ch’an schools. In Japan Pure Land adherents would remain independent from other traditions, competing with populist sects such as that of Nichiren, and splintering into several sub-sects.

Amitabha Sutra: One of the main sutras in the Chinese Pure Land sect. It is said to be the only sutra Shakyamuni preached without being asked, and one of the most popular sutras in China.

Amitayus (S): Tibetan: tse pa me, “Boundless Life.” Particular or reflexive form of Buddha Amitabha, to which is attached the idea of longevity. The embodiment of infinite life and therefore the focus of the life practices that remove the possibility of untimely or premature death. He brings about a healing of sicknesses, degeneration and imbalances in the five elements of the body due to karma, excess and unclean living. He is often depicted as ruby red, less frequently depicted as white. His two hands rest in his lap in the mudra of equanimity with the palms facing each other holding the Vase of Life, that is filled with the nectar of immortality. It is only in the Tantric Buddhism of Tibet and Japan that Amitayus and Amitaba are considered different deities.

Amoghasiddhi (S): Tibetan: Donyo Drupa. Buddha of Unfailing Accomplishment; Lord of the Karma Family, the fifth of the Dhyani or Transcendental Buddhas that embody the five primordial wisdoms. Lord of the Karma Buddha family, he is seated upon a lotus supported by shang-shang birds (S. garuda). Associated with the wisdom that achieves all, the transmutation of the poison jealousy, the color green, and the aggregate of volition, Amoghasiddhi is associated with the north of the ground of Prakuta Buddha, or Karmasampat, (T. la rab zog pa) “success in evolution.” His recognition symbol is the double dorje (visvavajra), representing the wisdom of all-accomplishing activity. His power and energy are both subtle, their dynamics often hidden from conscious awareness. Amoghasiddhi is Lord of the Supreme Siddhi — the magic power of enlightenment which flowers in Buddha Activity. In this way the inner and outer world, the visible and invisible are united as body is inspired and thegreat spirit of bodhicitta spontaneously embodies. Amoghasiddhi is depicted with emerald-green skin, his left hand resting in his lap in the mudra of equipoise and his right hand at chest level facing outwards in the fearless (S. abhya) mudra of granting protection. He is often depicted in union with his wisdom consort Damtsig Drolma — Green Tara, who embodies the pure element of air.

amrita (S): Tibetan: dud’tsi. Nectar of Immortality. The visualized flow of divine bliss which streams down from the sahasrara chakra when one enters very deep states of meditation.

Angulimala (S): ‘Rosary of Fingers’ An incredible Dharma story illustrating – on the down side the danger of having great devotion to the wrong guru and on the up side the possibility of transformation for anyone. To fulfill his commitments under a perverse teacher, Angulimala murdered those unlucky enough to wander into his corner of the jungle on the outskirts of Sravasti. He killed 999 people and made a rosary out of their finger bones. He was prevented by the Buddha from killing his thousandth victim, which he believed would lead him to liberation. After his encounter with the Buddha, Angulimala was eventually able to purify his mind and become an arhat.

animal realm: One of the six realms of conditional existence, where consciousness is consumed by brute ignorance and the struggle for survival.

annuttara samyak sambodhi (S): Perfection of complete enlightment — an attribute of every Buddha. In the Kagyu, Sakya and Gelug schools, this the highest, correct and complete or universal knowledge or awareness, the perfect wisdom of a Buddha.

anuttarayoga (S): Tibetan: la me gyu. This term refers to the higher tantras of the Kagyu, Sakya and Gelug schools. Practiced as the Mahayoga in the Nyingma school. The highest of the four levels of Vajrayana teachings. The three lower tantra classifications are Kriya, Carya and Yoga (the three Outer Tantras of the Nyingma school.) There are three divisions:

1. Pitriyoga or Father (Method) tantra.

2. Matriyoga or Mother (Wisdom) tantra.

3. Advityayoga or non-dual tantra.

anuyoga (S): Tibetan: je su naljor. ‘further union’ Second of the Nyingma three inner tantras and eighth of the Nine Yanas (vehicles). Emphasis is placed on the Perfection Phase, especially practice on the channels and winds. Based in tantras associated with Vajrasattva, Vimalakirti and King Dza. These teachings also involve visualizations wherein the deity is generated instantly (as compared to gradually as is done in the lower tantras).

appearances: T. nang wa. Literally, ‘lighting up’ Phenomena. Every thing we perceive in the world, beings, situations – are projections of the mind and in essence no other than the expanse of pure awareness. All appearances (mental and sensory phenomena) arise from a single source clear of the mind – its dynamic power. Manifestation derives from the same root as mani. Ignorance and attachment of the real situation support the foment of dualistic views, the intertia of karmic obscurations and negative habit patterns; appearances, including the perceiver are viewed dualistically and not recognized for what they are. Pure appearances are an expression of the dynamics of primordial wisdom: undisturbed by the obscuring operations of duality and world-forming karmas.

Arhat (S): Tibetan: dra bcom pa. “Foe destroyer.” A person who has destroyed his or her delusions and attained liberation from cyclic existence. The Arhat represents the Theravada ideal, one who has experienced the cessation of suffering by extinguishing all passions and desires and is thus free of the cycle of rebirth. According to Mahayana Buddhism, the arhat still has yet to achieve the ultimate goal; he has realized the emptiness of self, but has not yet refined this understanding to the point where he also realizes the emptiness of phenomena. By emphasizing his own salvation, the arhat has yet to attain full Buddhahood, as he has not yet awakened his compassion by working for the salvation of all beings. Stream-enterer, once-returner, and never returner are the first three stages on the path which lead to the realization of the arhat, which is considered the final goal of Sravakayana.

Aryadeva (S) noble shining one c. 375, Born spontaenously of a lotus (as was Padmasambhava) in Sri Lanka. Met Nagarjuna on pilgrimage and became his devotee. Matrceta, the poet, was a Brahman convert after debating Aryadeva at Nalanda. His student was Rahulamitra who taught Nagamitra who taught Samgharaksita who passed these teachings to Buddhapalita and Bhaviviveka.

Asanga: (S): Tibetan: Thok-me. “Without Attachment.” Fifth century Indian pandit abbot of Nalanda who met Buddha Maitreya after twelve years of seemingly fruitless practice in a cave around Vulture Peak. Receiving the Method lineage teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha directly from the future Buddha, Maitreya, he re-transcribed them in the form of five works known as the “Five Treatises of Maitreya” Founder of the Cittamatra, or the “Mind Only School” of Buddhist tenets.

ashok: Rose.

Ashoka: Buddhist monarch, c. 300 BCE, the third emperor of the Mauryan Dynasty, who unified most of India under his rule and fostered the dissemination of Buddhism. It is said that the Third Council was held during his reign. Ashoka set the model for many other rulers who sought to govern in accordance with Buddhist philosophy.

asura (S): Evil spirit; demon. Tibetan: lha ma yin. Opposite of sura: “deva; god.” Demi-gods. who do battle with the gods for the fruits of the wish-fulfilling tree. They do have access to the roots, from which they derive medicines to heal their wounds and continue fighting their lost cause. Also called the titans, these powerful beings embody the effects of prolonged envy. Non-physical being of the lower astral plane, Naraka. Asuras can and do interact with the human realm, causing major and minor problems in people’s lives. Like sentient beings in the other five realms, asuras are not permanently in this state.

Atisha (T): [982-1054] Sanskrit: Dipamkara. Also, Jowo Atisha. Indian Buddhist Master and scholar who spent 12 years in Sumatra and in 1042 went to Nepal and Tibet, where he exerted enormous influence. A main teacher at the university of Vikramasila who after traveling to Indonesia, received bodhicitta teachings from Dharmakirti (Lord of Suvarnadvipa). He spent his last years in Tibet as a teacher and translator. His disciples founded the Kadampa school. Also known as Dipamkara (S) or Jowo Atisha (T).

Atiyoga (S): Tibetan: shin tu naljor. The highest of the Nyingma three inner tantras, the culmination of the Nine Yanas (Vehicles). Atiyoga corresponds directly to the Great Perfection. Atiyoga is said to be an expression of perfect harmony between appearance and openness (sunyata), the non-duality of space and awareness; it is about the direct realization of the intrinsic nature ofmind… pure and free from beginningless time. (Tarthang Tulku) Through Atiyoga, enlightenment can be achieved in a single lifetime by an ardent practitioner and results in a self-existent pristine awareness which recognizes the utter perfection of all experience. See Dzogchen

atman (S): In Hinduism, atman is the soul; the breath; the principle of life and sensation. The soul in its entirety as the soul body (anandamaya kosha) and its essence (Parashakti and Parashiva). One of Hinduism’s most fundamental tenets is that we are the atman, not the physical body, emotions, external mind or personality.

Auspicious symbols (Eight Auspicious Symbols): In Tibetan Buddhism, a series of symbols associated with the Buddhas: a gold fish; a parasol; a conch shell; the Knot of Eternity; the Banner of Victory; a vase; a lotus; the wheel with eight spokes.

Avalokitesvara (S): Tibetan: Chenrezi. “The Lord Who Looks Upon All Suffering” The Buddha of Compassion. Avalokitesvara is the embodiment of the compassion of all the Buddhas and is regarded by the Tibetan people as the progenitor of the race and guardian of the country. As a monkey, he mated with a rock ogress and gave birth to the Tibetan people. He is one of the two chief Bodhisattva emanations of Amitabha. As a sambhogakaya emanation of the Lotus (Padma) Family, he is one of the Three Protectors of the Tantra; the other two being Manjusri and Vajrapani. Through his sharing of mankind’s misery, he positions himself to help those in distress and is considered a savior. Chenrezi is usually depicted with white wisdom-light skin; either two or four arms, sometimes in his 1,000-armed form. In his four-armed form, he sits in the lotus posture, with hands clasped in prayer over his heart; his other right hand holds a crystal mala upon which he counts mantras, and his other left hand holds an open lotus flower that radiates blessings to all beings. He rescues all beings by hearing their suffering and cries for help.

His thousand-armed form is depicted standing and has eleven heads with three levels diminishing in size as they face outward and to either side, representing his all-penetrating gaze. Upon these nine heads is the wrathful head of the Bodhisattva of Indestructible Power, dark blue Vajrapani, whose unfailing dynamic strength and power assist Avalokitesvara in the benefit of beings. Vajrapani’s head is crowned with that of Buddha Amitabha, the Lord of the Lotus Family of whom Avalokitesvara is an emanation. The 1,000 arms represent the appearance of 1,000 Buddhas during this Eon of Light, whose compassion will guide beings from the darkness of ignorance and delusion into the light of Great Awakening. The eyes on his 1,000 hands symbolize his all-seeing compassionate gaze upon every being in existence throughout the past, present and future. He symbolizes infinite compassion (Karuna) for his refusal of accepting nirvana, which he considers limited and beside the point and instead chooses to reincarnate so he can help mankind. He has appeared in this world numerous times (in both male and female forms) and therefore plays many roles depending on which strand of Buddhism one follows. The Dalai Lama is a manifestation of Chenrezi.

In China, Avalokitesvara was originally depicted in male form, later as a female in the graceful form of Kuan Yin, the Goddess of Compassion or Goddess of Mercy. In folk belief, she keeps people safe from natural catastrophe and in various forms traverses the realms of existence to aid all beings.

Avatamsaka Sutra: Flower Adornment, Flower Garland, Flower Ornament (Cleary) Sutra, a teaching of the tathagatabarbha class given by Buddha Shakyamuni soon after his attainment of Buddhahood. The sutra has been described as a link between Yogacara and Tantra (Conze), evoking a universe where everything freely interprets everything else. With such images as the Jewel Net of Indra, like a vast web of gems each of us, each thing reflects all other things. This was the principal text of the Chinese Hua-Yen Flower Adornement School. These teachings grew from a system of commentaries and were transmitted to Japan as Kegon.

Ayodhya: Situated on the south bank of the river Ghagra or Saryu, Just 6 km from Faizabad, Ayodhya is a popular place of pilgrimage and temple cities long standing. This town is closely associated with Lord Rama, the seventh incarnation of Lord Vishnu. One of the seven most sacred cities of India, the ancient city of Ayodhya, according to the Ramayana, was founded by Manu, the law-giver of the Hindus. King Dasaratha ruled there peacefully for ten thousand years, and still had no son to succeed him. After performing an elaborate puja and fire offering to the Gods, his wife Kausalya gave birth to Lord Sri Rama, who the Lord Brahma had sent to earth as a human incarnation of the god Vishnu. In contemporary Hinduism, Rama, who is also called Ram, is often worshipped as God. For centuries, Ayodhya was the pride of the kings of the Surya or Ikshavaka dynasty, also known as the Raghuvansh, of which Lord Rama was the most celebrated king. With the death of the last king of the Raghuvanshis, Ayodhya fell into decadence. Today, Ayodhya has many beautiful temples, although practically nothing of that age remains in the city, and none of the ancient structures survive. Of the present temples, 35 are dedicated to Lord Shiva and 63 to Lord Vishnu.The place where Lord Rama was born is marked by a small temple. The site where, according to legend, Lord Rama was cremated, Lakshman Ghat and Sita Ghat is still visible, and there are also ancient earth mounds, Mani Parbat, identified with a stupa built by Emperor Ashok and Sugriv Parbat, identified with an ancien monastery. Remnants of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Islam can still be found in Ayodhya. According to Jain tradition, five Tirthankaras were born at Ayodhya, including Adinath (Rishabhadeva) the 1st Tirthankar.

B

Bamboo Grove: Pali: Veluvana; Sanskrit: Venuvana, The first monastery (Bodhi-mandala) in Buddhism located in Rajagaha. It was donated by the elder Kalanda and built by King Bimbisara of Magadha.

bardo (T): Sanskrit: Antarabhava, “between two.” In general, any interval. The Intermediate state, as between death and rebirth, as well as the space between thoughts or dream sequences. Bardo is usually used to indicate the transitions one has to pass through in approaching death and rebirth. A period of visions and dream-like experiences conditioned by non-physical resonances resulting from an intimate association with organic existence is part of the normal sequence of events preceding rebirth. However, bardo also stands for other special states of mind, not all of which are connected with death. In the west “bardo” is usually referred to only the first three of these, that is, the states between death and rebirth, during which an individual is believed wander for a period that lasts an average of – according to the Tibetan teachings – 49 days. These states are differentiated as follows:

1. Chikai bardo, intermediate state of dying, the dissolution of the elemental body and the moment of death; the death process; the interval from the moment when the individual begins to die until the moment when the separation of the mind and body takes place.

2. Chonyi bardo, intermediate state of reality; the interval of the ultimate nature of phenomena (Dharmata), when the mind is plunged into the naked revelation of its own nature. If unrecognized, this degenerates into peaceful and wrathful visions. This is the first phase of after-death experience.

3. Sipai bardo, becoming; intermediate state; the interval in which the mind moves towards rebirth.

These last three listed states are no more and no less illusory than dreams and ordinary waking consciousness.

4. Samten bardo , intermediate state of meditation; samadhi, deep concentration; state of meditative stability.

5. Milam bardo, intermediate state of dreaming; the dream state experienced in sleep and daydreams.

6. Kyene bardo, the interval between birth and death; intermediate state of ordinary consciousness; the waking state during the present lifetime.

bardo thödol (T): A text based on oral teachings by Padmasambhava and recorded in written form circa 760. After having been hidden as terma, the text was rediscovered (and extended) by the Terton Karma Lingpa in the 14th century. The text is part of the Kargling Zhi-khro collection of the Dzogchen tradition and shows traces of earlier and originally pre-buddhist Tibetan thought; indicated by symbolism and divinities that are part of the shamanic Bön religion. By way of misrepresentation of the text by Evans-Wentz (1878-1957), the Western reader has come to know this text as “The Tibetan Book of the Dead,” a translation that has misguided many readers. A much better translation by Trungpa and Fremantle is entitled”Liberation by Hearing During One’s Existence in the Bardo.” The text is read aloud (i.e. “liberation by hearing”) to someone in bardo, sometimes as pure instruction for meditation and, at the time of death, to guide the mind through the labyrinth of adventures ahead.

being: Sanskrit: bhava, lifer, becoming. Tibetan: srid pa; existence

believing faith: Sanskrit: abhisampratyaya.

bell: Sanskrit: ghanta. Tibetan: drilbu. Vajra handbell used in tantric practices symbolizing the all pervading wisdom-realizing emptiness. The bell is the female part of the Tantric polarity, symbolizing emptiness – boundless openness, the space of pure wisdom and the liberating sound of the Dharma. It is accompanied by another handheld object, a brass wand or dorje (Tibetan: diamond) – vajra in Sanskrit. The vajra scepter is the male part of the Tantric polarity, symbolizing effective means and Buddha’s active compassion. Originally it was associated with divine authority and power as the thunderbolt weapon of the King of the gods and Lord of Storms, Indra. In Tibet it came to represent the indestructible nature of diamond.

Bhadanta (S): “Most virtuous.” Honorific title apllied to a Buddha.

Bhadrayaniyah (S): A branch of the Hinayana sect Sthavirandin, developed from Vatsiputriyah.

bhaga (S): Luck, wealth, secret place, yoni.

Bhagavan (S): Tibetan: Chom Den De. An epithet frequently applied to the Buddha. It designates he who has vanquished the four demons, who possesses all the qualities and who is beyond the two extremes of existence and nihilism. This word designates then a perfectly accomplished Buddha.

Bhagavat (S): “World-Honored One.” Also, “Lord,” “Blessed One.” Honorific names of the Buddha.

Bhaisajyaguru (S): Tibetan: Sangye Menla. Healing Buddha, Medicine Buddha, who quells disease and lengthens life. His realm is the Eastern Paradise or Pure Land of Lapis Lazuli Light.

bhakti (S): Devotion. Surrender. Bhakti extends from the simplest expression of devotion to the ego-decimating principle of prapatti, which is total surrender. Emphasizes emotional control; the way to the divine through love.

bhakti yoga (S): “Union through devotion.” Bhakti yoga is the practice of devotional disciplines, worship, prayer, chanting and singing with the aim of awakening love in the heart and opening oneself to divine grace. From the beginning practice of bhakti to advanced devotion, called prapatti, self-effacement is an intricate part of Hindu, even all Indian, culture.

Bhante (P): Venerable Sir. A term of respectful address to an elder bhikkhu, used extensively in Theravadist communities.

bhava (P): State of existence of becoming, life.

bhavana (P): Cultivation.

bhavatanha (P): Craving, desire, thirst for being

bhiksu (S): Pali: Bhikku. Religious mendicant or monk of the order founded by Gotama Buddha. One of the four primary classes of Buddhist disciples, the male who has taken the monastic precepts. The other three are, bhiksuni (Pali: bhikkhuni), the monastic female; upasaka, the male who has taken the lay precepts; and upasika, the lay female. A ordained monastic who depends on alms for a living.

Bhrikuti (S): Tibetan: Jomo Khro Nye kan. A form of Tara, “she who has a wrathful frown.”

bhumi (S): Tibetan: Jyang-sa. “Ground.” One of the ten stages of realization and activity through which a Bodhisattva progresses towards Enlightenment. The ten bhumis are levels of awakening subsequent to the realization of emptiness: The Supremely Joyful; The Stainless; The Illuminating; The Radiant; The Difficult to Train For; The Manifesting; The Far Going; The Unwavering; The Excellent Intelligence; The Cloud of Dharma. Of the five paths, the first bhumi is identical with the path of seeing. Bhumis 2-9 are on the path of meditation. There are 10 bhumi levels which are distinguished in the Mahayana and 13 in the Mantrayana (Vajrayana) which represent the quintessence of buddhist teachings.

bija (S): Seed syllable. Mantra syllables, sounds that are symbols that enlightened beings use to communicate to Dharma practitioners, who also visualize them.

blessing: Sanskrit: adhisthana. Tibetan: Jin lap. Good wishes; benediction. Seeking and giving blessings. A more technical definition refers to a supplementary initiation into a specific deity practice based on having already received a major empowerment, e.g., the Vajrayogini initiation is a “blessing” based on the Chakrasamvara or Hevajra empowerments. An individual must receive the empowerment first before receiving the blessing initiation.

bliss: Tibetan: de nyam. In Vajrayana, there are four types of bliss:

1. blissful feeling – to be free from adverse conditions of disharmony.

2. conceptual bliss – to be free from the pain of concepts.

3. non-dual bliss – to be free from clinging to dualistic fixations.

4. unconditioned bliss – to be free from causes and conditions.

When the experiences of clarity, non-thought and bliss appear, a practitioner can become attached to these, thus giving rise to a hindrance called the “defect of meditation.” One who does not detach, strays into three states of existence (the realms of desire, form, and formlessness).

Blissful Pure Land: Sanskrit: Sukhavati. Tibetan: Dewachen.

Bod (T): The Ancient Tibetan word for Tibet, pronounced “Bo,” or “Po.” The word Bod may be derived from Bon.

Bodhgaya home of the (S): vajrasana (diamond seat) Tibetan: Dorje dan. Small town in northeast India where Shakyamuni Buddha’s six years of ascetic wandering culminated in full enlightenment. Present day site of the Mahabodhi Stupa. Formerly in the province of Magadha, today in the state of Bihar. The first Buddhas of each Dharma period manifest full enlightenment in Bodhgaya.

bodhi (S): Awakening. (T) Chang-chub. Traditionally translated as “enlightenment,” Bodhi is the opposite of ignorance. A consummate insight into reality which destroys mental afflictions and brings peace. As such, it is the goal of personal practice for the Buddhist, and the nurturing of bodhi in society in general his foremost interest.

Bodhicaryavatara (S.) Tibetan: Jang-chub sem pai spyod pa la jug pa. Written by the Mahayana poet and scholar Santideva in the 7th century AD. Shantideva was an Indian Buddhist monk. According to legend he was born a crown prince and left his royal life to adopt the spiritual path. He received visions and teachings from Manjusri in person before studying at Nalanda where he was viewed as a lazy monk until he was called before an assembly where he spontaneously delivered the Bodhicaryavatara and disappeared into the sky during what has become the Ninth Chapter. The Bodhicaryavatara is one of the world’s great masterpieces of religious literature. The work details the moral and spiritual discipline of one who wishes to become a bodhisattva. The Bodhicaryavatara contemplates the profound desire to become a Buddha in order to save all beings from suffering. In ancient times there were at least a hundred commentaries on the Bodhicaryavatara and its popularity has continued down to the present in Sri Lanka, India and in Tibet, where it is still widely read and studied. Santideva sets out what the Bodhisattva must do and become, what must be embraced and what is to be rejected; he also invokes the intense feelings of aspiration which underlie such a commitment, using language which has inspired Buddhists in their religious life from his time to the present.

Bodhicitta (S): Tibetan: Jang-chub sem. Also “bodhi mind.” Awakened heart, awakened mind, enlightened thought. The mind or spirit of enlightenment. It is with this initiative that a Buddhist begins his path to complete, perfect enlightenment. There are various kinds of bodhicitta: 1) At the sutra level, Relative Bodhicitta is the aspiration to practice the six paramitas and free all beings from the sufferings of samsara. It involves two parallel aspects, aspiration and action: first comes the aspiration or determination to achieve Buddhahood. According to Longchenpa, the aspiration to awaken corresponds to contemplating the four immeasurables; desiring that all beings be sustained by awakening to boundless love, compassion, joy and equanimity. The second type of bodhicitta is called actualizing and consists of the practice of the six paramitas. The difference between the first and second kinds has been compared to the enthusiasm and preparation made before a journey and then the actual voyage, the action of putting this quality of compassion into practice. 2) Absolute Bodhicitta is an awakened mind that sees the uncompounded emptiness of phenomena. In Dzogchen terminlogy Bodhicitta is the original state, our True Nature. “Jang” implies purified, purity, clear and limpid since the beginning, meaning that nothing needs to be purified or altered. “Chub” means perfected or expanded and implies there is no need for further improvement. “Sem,” or “mind,” is the state of consciousness of which is the agency for the manifestation of this bodhi in the world. Thus bodhcitta is the original state, the true condition of which is immutable. The precepts associated with bodhicitta consist of three main points: 1) the ten non-virtues must be abandoned, 2) the ten virtuous actions that are antidotes must be applied, and 3) the ten paramitas are to be engaged.

Bodhidharma (S) [470-543 c.e.] Indian monk and 28th Patriarch who left India for China in about 520 c.e. and became the First Patriarch of Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism.

bodhi nana (P): Also “sabbannuta nana.” Supreme Enlightenment; the all comprehending wisdom. Corresponds to bodhicitta.

bodhisattva (S): Tibetan: Jang-chub sempa. Awakened Being. Shakyamuni Buddha used this term to describe himself when he was seeking enlightenment. Bodhi means “Enlightenment” and sattva means “sentient” or “conscious. Thus “bodhisattva” refers to a “sentient being of great wisdom and enlightenment.” The bodhisattva’s goal is the pursuit of Buddhahood and the salvation of all. The bodhisattva cycles through rebirths to help liberate beings from suffering and further establish the Dharma in the world. The bodhisattva path and discipline, generally accepted by Mahayana practitioners, is based in the aspiration, generation and application of the bodhicitta. Bodhisattvas are awakening beings whose realization is not yet that of the Buddhas. The bodhisattvas develop the intention to reach the state of Buddha, in order to release all sentient beings from the suffering of the cycle of existence. They work with this intention while developing compassion and renouncing the stain of any personal interest. Accompanied by Joyful effort and the other paramitas, this altruistic attitude permits one to slice through the thick inertia of egocentric habit energy and constitutes the energy of awakening. The bodhisattva works for the good of beings until the end of samsara through the practice of the ten perfections – or paramitas. There are ten stages in the Bodhisattva process. A Mahasattva is one who has reached the tenth stage but delays entering complete Enlightenment so as to help others. See bhumi; Four Great Vows.

Bodhi tree: Also, Bo Tree. Tree beneath which the meditating Gautama sat before he achieved enlightenment. According to tradition this was an Asvattha tree, though there is no historical evidence to support this belief. It is widely believed to have been a Pipal tree, ficus religiosa, a large deciduous tree found in uplands and plains of India and Southeast Asia. To this day, Buddhists make rosaries (malas) from the seed and plant the tree outside of temples. Even the leaf is revered and sometimes carried as a charm. The fruit contains serotonin and may have been used as an entheogen, although it is currently revered but rarely consumed. Although a tropical tree, it can thrive as a houseplant, and is easy to grow as other ficus species. This fast growing tree usually begins as an epiphyte (air plant, grows on trees) but develops roots to support its height of 90-plus feet. Has purple figs, red flowers, and is different from other species, because of its slender, long leaf tip. See Pipal.

Bodpa (T): Tibetan word for “Tibetan,” both as a noun and as an adjective.

body energy: In the Tibetan view, there are six types and are referred to as winds (T. rlung): All-pervading (kyab-yed); Ascending (gyen-gyen); Evacuating (tur-sel); Fiery (me-nyam); Life-supporting (rok-zin); body-speech-mind (go-sum).

Bon / Bonpo (T): invocation – recitation. Tibet’s pre-Buddhist, animist religion. a general heading for various religious currents in Tibet before the introduction of Buddhism by Guru Padmasambhava in the 8th century. The word Bonpo originally referred to shamanic priests who performed certain rites such as burial and divination. In the 11th century Bonpo became a name for an independent school that distinguished itself from Buddhism in claiming to preserve the continuity of the old Bön tradition. Tibetan history states that in pre-Buddhist times the kings were protected by three kinds of practitoners, the shamanic Bonpo’s, the bards, and the riddle game pratictitoners. The Bonpo were responsible for the exorcism of hostile forces. Their roles grew and expanded over the years until three different aspects of their duties were distinguished.

Revealed Bon represents the first stage. Practitioners of the Bön tradition employ various means to “tame demons below, offer to gods above and purify the firehearths in the middle” using methods of divination to make the will of the gods known. With the murder of an important king named Trigum the stage called Irregular Bon came about. At this time the main duty of the Bon was to bury kings. This time also brought an elaboration of the philosophical system because of contact with non-Tibetan Bonpos from the west. In the phase known as Transformed Bon major portions of Buddhist teachings were taken into this system, still without giving up the elements of the folk religion. This took place between the 8th and the 10th centuries.

bumpa (T): Ewer or ritual vase used during special ceremonies, in particular during tantric empowerments.

Buton (T): [1290-1364]. Sakya scholar-historian and yogi who finalized the compilation of the Tibetan Buddhist canon. One of the lineage lamas of the Six Yogas of Naropa. Author of “The History of Buddhism in India.”

Brahma (S): The creator god. One of the three major deities of Hinduism, along with Visnu (Vishnu) and Siva (Shiva). Adopted as one of the protective deities of Buddhism.

Brahma Net Sutra (Brahmajala Sutra): Sutra of major significance in Mahayana Buddhism. In addition to containing the ten major precepts of Mahayana (not to kill, steal, lie, etc.) the Sutra also contains 48 minor injunctions. The major and minor precepts constitute the Bodhisattva Precepts, taken by most Mahayana monks and nuns and certain advanced lay practitioners (upasakas).

Brahmin (S): The highest of the four Indian castes at the time of Shakyamuni. This priestly class served the original creator god Brahma through regular offerings and observances as the keepers of the Vedas.

Buddha (S): Awakened One. Title applied to the prince of the Sakya clan, Siddharta Gautama upon reaching perfect enlightenment. In everyday talk it is used as the name of the founder of Buddhism. ‘Buddha’ is the primary title of those who have entirely awakened to the Dharma, and especially those who awaken to it during an era when the Dharma is not presently manifest, and so function as the means for the introduction of the blessings of the Dharma into the world. In the cosmic vision of millions of world systems to be found in Mahayana scriptures, ‘buddhas’ refer to other buddhas who exist simultaneously throughout the universe, as well as the past and future buddhas of this world.

Buddha of Limitless Light: Sanskrit: Amitabha. Tibetan: Öpame. His western paradise is Dewachen (S. Sukhavati), the pure land of highest bliss where the faithful are reborn in conditions extremely conducive to accomplish their spiritiual aspirations. See Amitabha

Buddhadharma (S): “Teaching of Enlightenment.” Originally apllied to designate the teaching of Shakyamuni Buddha. Over time, this has been replaced by the term “Buddhism.”

Buddhaghosa (P): A famous buddhist writer who visited Ceylon and wrote the famous Visuddimagga / (Path of Purification).

Buddha-ksetra (S): Buddhaland. In Mahayana, the realm acquired by one who reaches perfect enlightenment, where he instructs all beings born there, preparing them for enlightenment, e.g. Amitabha in Sukhavati-Dewachen (Western Paradise); Bhaisajyaguru (Medicine Master Buddha) in Pure Land of Lapus Lazuli Light (Eastern Paradise).

Buddha Nature: Sanskrit: tathagatagarbha. Tibetan: sangye kyi nyingpo. The potential every sentient being has to realize Buddhahood. The Buddha essence within each being which is uncovered through enlightenment. The mind’s innate potential to achieve enlightenment; the clear, originally pure basis for attaining enlightenment that exists in all living beings. The following (and many more) are synonomous: True Nature, Original Nature, Natural State, Dharma Nature, True Mark, True Mind, True Emptiness, True Thusness, Dharma Body, Original Face. The Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen: According to the Mahayana view, [buddha-nature] is the true, immutable, and eternal nature of all beings. Since all beings possess buddha-nature, it is possible for them to attain enlightenment and become a buddha, regardless of what level of existence they occupy. The answer to the question whether buddha-nature is immanent in beings is an essential determining factor for the association of a given school with Theravada or Mahayana, the two great currents within Buddhism. In Theravada this notion is unknown; here the potential to become a buddha is not ascribed to every being. Having already been visited by a Buddha, they are of the opinion that the highest attainment possible is the mind of the arhat. By contrast the Mahayana sees the attainment of buddhahood as the highest goal; it can be realized through intense cultivation of the bodhicitta revealing the inherent buddha-nature of every being.

Buddhas of Confession: Or, the 35 Buddhas of Confession. Each of the 35 Buddhas has at the same time the capacity to eliminate negative actions and obstacles to the practice of Dharma. The recitation of the Sutra of Three Accumulations, the prayer of confession in front of 35 Buddhas is a particularly effective method to purify of any failures. This is usually accompanied by prostrations.

Buddhist cosmology: Original (Hinayana/Theravada) cosmology, there is only one world, in the center of which lies mount Meru with mountain ranges and four main continents. The southern continent, Jambu (India or Earth) is the place where we all live. The other continents are inhabited, but beings can mature best only in Jambudvipa. All world systems have a beginning and an end, and while beings’ good karma can fill the world with good impressions, their karma creates the specific phenomena and ultimately destoys it. Mahayana cosmology also employs the model of Mount Meru surrounded by four major continents and eight lesser ones, but there are an infinite number of worlds, which are arranged in a hierarchical manner. These worlds are created by karma as well as by the compassion of the buddhas and the vows of the bodhisattvas. Worlds are created and destroyed until all beings are liberated from the sufferings of cyclic existence. Vajrayana offers two versions: The Kalachakra integrates macrocosm and microcosm into a coherent whole and includes an astrological system. Mahamudra and Dzogchen teachings dismiss cosmology with “Non-Cosmology” and define the universe as primordial mind. All phenomena and experience are expressions of this.

buji (J): “No matter.” Zen term describing an attitude acquired toward the Dharma, when a practitioner mistakenly believes that practice is not necessary since all sentient beings are originally buddhas. See eternalism

Bulug (T): Sub-school maintaining the tradition of Buton Thamche Khyenpa, more commonly known as the Zhalupa (no longer extant).

Buton (T): [1290-1364]. Sakya scholar-historian and yogi who finalized the compilation of the Tibetan Buddhist canon. One of the lineage lamas of the Six Yogas of Naropa. Author of “The History of Buddhism in India.”

C

Caturmukha (S): Tibetan: Shalshipa. “Four-Faced-One.” The form of Mahakala related to the Guhyasamaja Tantra and a principal protector of the Sakya School. Usually depicted as Brahmarupa (Dram ze) Mahakala.

chakra (S): Tibetan: Khorlo. “Wheel.” Any of the nerve plexes or centers of force and consciousness located in the energy body of man. These are junctures of force where the three primary meridians tie into the secondary network of channels. In the physical body there are corresponding nerve plexuses, ganglia and glands which are dynamically related to the condition of these chakras. As per Hinduism, there are seven principal chakras which appear psychically as colorful, multi-petalled wheels or lotuses. In the Tibetan tradition, only five chakras are recognized as they consider the lower two (muladhara and svadhisthana) as well as the upper two (ajna and sahasrara) to be fused into one chakra apiece. They are situated along the spinal cord from the base to the cranial chamber. As seats of instinctive consciousness, they are the physical origin of emotions and states of meditation, etc. The seven upper chakras, from lowest to highest, are:

1. muladhara (base of spine): memory, time and space

2. svadhishthana (below navel): reason

3. manipura (solar plexus): willpower

4. anahata (heart center): direct cognition

5. vishuddha (throat): divine love

6. ajna (third eye): divine sight

7. sahasrara (crown of head): illumination, divinity

In Tibetan Buddhism there are usually five such chakras named, located at the top of the head, the throat, the heart, the navel and the secret center. They constitute the locations where the channels juncture as that the three principal channels are found to be in contact at each of these centers. Certain meditations utilizing seed syllables aim at provoking bliss fused with emptiness (i.e. the four joys) in these centers.

Chakrasamvara (S): Tibetan: Khorlo Demchog. Principal meditation deity of the Chakrasamvara cycle of tantras. He is a heruka, a wrathful yidam of the Lotus family and an important Buddha in the six yogas of Naropa. Chakrasamvara is the primary Yidam of the Kagyu tradition that finds its origin in the meditation of the 84 Mahasiddhis of India. It passed to Tibet from the great siddha Naropa, to his disciple Marpa, to Milarepa and spread throughout the various meditative traditions of the Gelug and Sakya. A tantric form of Avalokitesvara, his body is blue in color with four faces, each looking in one of the four cardinal directions and sporting 12 arms. He is often depicted in his more simple one-faced, two-armed form. He is in union with his wisdom consort Vajravarahi (Diamond Sow). She is as simple as he is complex. She holds a skullcap in her left hand and a vajra chopper (drigung) in her right, both behind his back. Their embrace symbolizes the union of wisdom and skillful means. They symbolize the sameness in the distinctions of relative truth and the non-distinctions of absolute truth.

Chakrasamvara Tantra: Tibetan: Khorlo Dompagyu. Principal anuttarayoga tantra of the wisdom (mother) classification.

Ch’an (C): Chinese development of Indian Mahayana Buddhism; deriving from the word dhyana or meditation, the Chinese abbreviated it to ch’an-na, “meditation.” This became Zen when it was imported to Japan, and in Korea, Son. The Ch’an School was established in China by Bodhidharma, the 28th Patriarch who brought a Mahayana tradition of the Buddha-mind from India. Disregarding ritual and sutras, this school professes sudden enlightenment which is beyond any mark, including speech and writing. Probably the most common form of Buddhism in the West, Zen practitioners usually devote themselves to monastic life, as accomplishment requires extensive periods of meditation. It concentrates on making clear that reality transcends words and language and is beyond rational analysis and logic. To accomplish this, this tradition makes use of the koan, zazen and sanzen. This school is said to be for those of superior roots. See Zen

Chandrakirti (S): Tibetan: Lawarepa. Sixth century Indian pandit and disciple of Nagarjuna, who presented Nagarjuna’s exposition of Madyamika (Middle Way) in the Prasangika-Madyamika form which is still studied in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries today. When asked about present and future lives and the workings of karma. He replied, “Watch how you breathe.”

ch’an-na (C): meditation

chang (T): Beer brewed from rice, millet or corn.

Changchub Dorje (T): [1703-1732] The twelfth Karmapa.

channel: Sanskrit: nãdi. Tibetan: tsa. A constituent of the vajra body through which subtle energy winds (lung) and drops (tigle) flow. The central, right, and left are the major channels. The central channel (Sanskrit: avadhuti. Tibetan: tsa dhuma) is the most important of the thousands of channels of the subtle body. During inner-fire meditation (tummo) it is visualized as blue, running just in front of the spine, starting at the brow chakra and ending four finger-widths below the navel. Various syllables are visualized, both seated at the chakras and travelling within the channel system Such practices should only be attempted after proper transmission and teaching, after completing preliminary practices and achieving stability in generation-phase practice.

Channels, Winds, and drops: Sanskrit: Nadi,(channel) Prana, (vital energy) bindu (or essence elements) // Tibetan: rTsa, (roots/channels) rLung (winds), tig-le (drops, essence elements). Also known as winds, drops and channels. The three principal channels of the body are known in Tibetan as Roma, Uma and Kyang-ma, and in (S. Lalana, Avadhuti and Rasana). The entire body is filled with a network of canals (72,000 by tradition) in which subtle winds circulate, that is to say the energy of solar and lunar forces, emotions, and mind. There are three principal pathways, the primary meridians which run the length of the torso and culminate in the crown chakra. Like branches off the main trunk, the other channels develop from these during the time of the formation of the fetus; these dynamics are reabsorbed into the primary meridians at the time of death. One of the goals of tantric meditation is the concentration of the winds and the fluids in the central canal (Tibetan: Uma), thus provoking the experience of the fusion of bliss with emptiness, which is the natural state of the mind of the Buddhas.

charity: Transcendent generosity, the first Paramita. There are three kinds of charity in terms of goods, doctrines (Dharma) and courage (fearlessness). Out of the three, the merits and virtues of Dharma charity is the most surpassing. Charity done for no reward here and hereafter is called pure or unsullied, while the sullied charity is done for the purpose of personal benefits. In Buddhism, the merits and virtues of pure charity is considered the best. See Paramita, Dana

Chenrezi (T): Also Chenresig, Chenrezig; and Avalokitesvara (Sanskrit). The Buddha or Bodhisattva of Compassion. The embodiment of the infinite compassion of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. His Holiness the Dalai Lama is recognized as the human incarnation of Chenresig. See Avalokitesvara

chi (Chinese, “breath or energy”): Sanskrit: prana. Tibetan: lung. Subtle energy or life force. In Taoism, chi is the cosmic energy that permeates all things. Within the human body, chi is seen as the vital force closely associated with the breath. During the act of breathing, in addition to oxygenating the blood with the outer breath (wai chi), one breathes in with the inner breath (nei chi) the surrounding cosmic energy to resupply the inner chi or life force of the body. Chi, Ching and Shen are the three life energies that make up the human being. Ching is the reproductive energy, chi is the vital energy of the body, and the shen is the spirit or soul. Taoist practices seek to transform the ching to chi, and the chi into shen. See prana, lung, channel

Chinese Buddhism: Comes in ten flavors — schools, traditions or sects. They are: 1. Kosa; 2. Satyasiddhi; 3. Madhyamika; 4. Tien Tai; 5. Hua Yen; 6. Dharmalaksana; 7. Vinaya; 8. Cha’an; 9. Esoteric; 10. Pure Land.

Chöd (T): “Cutting, Severance.” The charnal ground practice in which the practitioners severs attachment to his or her corporeal form This practice originated in the eleventh century with the Indian adept, Padampa Sangye, and his heart student, the Tibetan woman Macig Labdron. a great Tibetan yogini, c. 1100. The teaching spread widely in India and is now practiced, to a greater or lesser degree by all schools of Tibetan Buddhism. Chöd practice always begins with Phowa in which the consciousness of the practitioner is visualized as leaving the body through the crown chakra and taking the form of the female deity Vajrayogini. In the form of Vajrayogini, the practitioner then visualizes the ritual purification offering of his/her own body to the Four Guests (the Three Jewels, Dakinis and Dharmapalas, beings of the six realms, and the ever present miscellaneous local spirits and demons). The ceremony can be long, involving separate offerings to each group or abbreviated; many variations exist. It is a very powerful practice when done correctly. Spirits are summoned by the blowing of the kha-ling, or thigh-bone trumpet, and beating of the damaru (two headed drum). The complete practice of Chöd is very difficult, demanding a high degree of equanimity, compassion and renunciation.. Lineages: Shijed, or Zibyed, Zhi-je (zhi-byed-pa) “Pacifying Pain.”

Chö-nyi (T): Dharmata, the Space of reality.

chorten: (T): Sanskrit: stupa. Symbolic representation of the Buddha’s mind. Originally derived from cairns and burial mounds for great beings in ancient Asia, it became formalized during the Buddha’s time and is now a very common monument to the sacred seen throughout the Buddhist world, chortens often have a wide, square base, rounded mid-section, and a tall conical upper section topped by a moon and sun. They usually hold relics of enlightened beings and may vary in size from small clay models to vast, multi-storied structures which contain a temple. See stupa

Chö-ying (T): Spatial dimension, universal realm of phenomena or dharmadhatu. This term signifies the unobstructed play of Wisdom Mind in the limitlessness of Wisdom Space.

chu-len (T): Literally, “taking the essence.” Chu-len pills are made of essential ingredients; taking but a few each day, accomplished meditators can remain secluded in retreat for months or years without having to depend upon normal food.

citta (S): (C. Hsin) Heart and mind, the terms being synonymous in Asian religious philosophy. 1) The Conditioned (compounded) mind describes all the various phenomena in the world, made up of separate, discrete elements, “with outflows,” karmically interdpendent, with no intrinsic nature of their own. Conditioned merits and virtues lead to rebirth within samsara, whereas unconditioned merits and virtues are the causes of liberation from the round of unconscious birth and death. On the personal level, citta is that in which mental impressions and experiences are recorded. 2) Seat of all conscious, subconscious and superconscious states, and of the three-fold mental faculty, (Sanskrit: antahkarana) consisting of buddhi, manas and ahamkara. Also: thought, thoughtfulness, active thoughts, mind, state of consciousness. See Unconditioned Mind; consciousness

Cittamani Tara (S): The highest yoga tantra aspect of the female deity Tara.

circumambulations: A walking meditation in which the practitioner reapeatedly circles a sacred site while practicing a sadhana or mantra meditation. One might circumambulate a monastery or a temple, a sacred lake like Pema Tso in northern India, or even a sacred mountain like Kailash, in Tibet or Turtle Hill in southern middle Tennessee. Thouands of people make an annual pilgrimage to the holy shrine of Kailasha, some of them taking several days to circumambulate the mountain once.

clarity: The unobstructed, naked radiance of awareness. There are three types: Spontaneous Clarity, the state being free from an object; Original Clarity does not appear for a temporary duration; Natural Clarity, not made, unfabricated. Along with these three experiences of clarity, Non-thought and Bliss may naturally appear, although attachment to which these is considered a hindrance counted among the “Defects of Meditation” Leading one into the three states of existences (Realm of Desire, Form, Formlessness).

clear light: Sanskrit: prachãsvara. Tibetan: ‘od-sal. The mind’s intrinsic nature. The subtlest level of that which is fully revealed at the time of death but is usually not recognized unless the person has engaged in the practice of meditation and tantra. This primordial light illuminates the Universe at its deepest level. Perceiving the Clear Light is the most fundamental level of consciousness. Arriving at this level, one can view all phenomena as a manifestation of this pure energy. This clearness or luminosity is one of the two essential characteristics of the unborn, uncreated nature of the mind, with a quality of natural irradiation which projects and simultaneously knows the constantly arising energy display we call mind. The other characteristic is emptiness of anything that could be said to exist. Clariy and emptiness are indissociable in the ultimate nature of the mind.

Clear Light Meditation: One of the Six Teachings of Naropa.

cognitive base: Sanskrit: ayatana. Tibetan: kye-che. The six senses (sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch, mental consciousness) and the six objects of the senses (forms, sounds, odors, sensations, thoughts) that act as the bases for consciousness. KPSR has described the dynamic nature of the ayatanas as being like an eruption or a bursting forth. See Six Consciousnesses

compassion: Sanskrit: karuna. Tibetan: nying je. The wish that all beings be released of their physical and mental sufferings and afflictions. Preliminary to the development of non-dual bodhicitta, it is symbolized by Avalokiteshvara, who embodies the infinite compassion of a buddha. Counted among the Four Immeasurables.