Documentos

Amrita

Amrita (Skt. Amrita ; Tib. བདུད་ རྩི་ , dutsi , Wyl. Bdud rtsi ) – a palavra sânscrita amrita significa “imortal”; no tibetano é བདུད་ རྩི་, dütsi , porque, diz-se, “é o remédio que supera o temível estado de morte”.

Amrita (Skt. Amrita ; Tib. བདུད་ རྩི་ , dutsi , Wyl. Bdud rtsi ) – a palavra sânscrita amrita significa “imortal”; no tibetano é བདུད་ རྩི་, dütsi , porque, diz-se, “é o remédio que supera o temível estado de morte”.

O Tantra do Ciclo Secreto diz:

-

-

Para samsara que é como mara (བདུད་, dü)

Quando o elixir (རྩི་, ts ) da verdade do Dharma é aplicado,

É chamado néctar ( བདུད་ རྩི་ , dütsi).

O néctar medicinal da amrita cura e repara os siddhis, ou realizações, em todas as dimensões.

O décimo terceiro dalai-lama escreveu: “Todos os siddhis, diz-se, incluindo a realização do corpo vajra da imortalidade, vêm como resultado das qualidades da amrita”. Os Oito Volumes no Néctar explicam:

-

Curando as quatrocentas e vinte e quatro doenças

E destruindo as quatro maras,

É a essência suprema, o rei dos remédios.

- Fonte: http://www.rigpawiki.org/index.php?title=Amrita

-

6 Paramitas

Paramita (em sânscrito) ou Parami (em pali): “Perfeição” ou “Transcendente” (lit. “Que alcançou a outra margem”). No budismo, chama-se de paramitas as perfeições ou culminações de certas práticas. Tais práticas são cultivadas por bodhisattvas para percorrer o caminho à iluminação.

Paramita (em sânscrito) ou Parami (em pali): “Perfeição” ou “Transcendente” (lit. “Que alcançou a outra margem”). No budismo, chama-se de paramitas as perfeições ou culminações de certas práticas. Tais práticas são cultivadas por bodhisattvas para percorrer o caminho à iluminação.

As Seis Paramitas, ou Seis Perfeições transcendentes(Skt. ṣaṭpāramitā; Tib. ཕ་རོལ་ཏུ་ཕྱིན་པ་དྲུག་, parol tu chinpa druk; Wyl. pha rol tu phyin pa drug), compreendem o treinamento do bodhisattva, que é a bodhichita em ação.

- Generosidade (Skt. dāna; Tib. སྦྱིན་པ་, jinpa): cultivar a atitude de generozidade.

- Disciplina (Skt. śīla; Tib. ཚུལ་ཁྲིམས་, tsultrim): abstenção de danos.

- Paciência (Skt. kṣānti; Tib. བཟོད་པ་, zöpa): capacidade de não ser perturbado por nada.

- Diligência (Skt. vīrya; Tib. བརྩོན་འགྲུས་, tsöndrü): encontrar alegria no que é virtuoso, positivo ou saudável.

- Concentração Meditativa (Skt. dhyāna; Tib. བསམ་གཏན་, samten): não se distrair.

- Sabedoria (Skt. prajñā; Tib. ཤེས་རབ་, sherab): a perfeita discriminação dos fenômenos, todas as coisas conhecíveis.

As primeiras 5 paramitas correspondem à acumulação de mérito, e a sexta paramita à acumulação de sabedoria. A sexta paramita pode ser dividida em mais 4 paramitas, resultando em Dez Paramitas.

7. Meios Hábeis (Skt. upāyakauśalapāramitā; Tib. ཐབས་ལ་མཁས་པ་, tap la khepa; Wyl. thabs la mkhas pa),

8. Força (Skt. balapāramitā; Tib. སྟོབས་, top; Wyl. stobs),

9. Aspiração (Skt. praṇidhānapāramitā; Tib. སྨོན་ལམ་, mönlam; Wyl. smon lam) and

10. Sabedoria Primordial (Skt. jñānapāramitā; Tib. ཡེ་ཤེས་, yeshe; Wyl. ye shes).

A maneira de dividir as paramitas em dez é particularmente relacionada aos ensinamentos sobre os bhumis que descrevem a progressão de um bodhisattva, em que cada uma das paramitas é sucessivamente aperfeiçoada em cada um dos dez bhumis .

Referencia https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paramitas

Oito Stupas

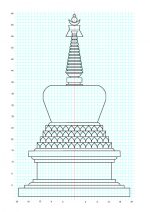

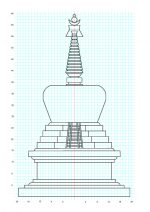

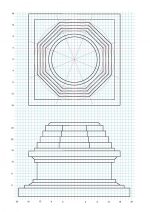

(1) Stupa of Heaped Lotuses

(1) Stupa of Heaped Lotuses

Commemorates the Buddha’s birth at Lumbini, where he took seven steps in each of the four directions, from which lotuses sprang.

The Lotus Blossom Chorten

The Chorten is also known as the Chorten of heaped Lotuses. It refers to the birth of the Buddha. At birth Buddha took seven steps in each of the four directions- East, South, West and North. In each direction lotuses sprang, symbolising the four immeasurable of love, compassion, joy and equanimity.

The four steps of the basis of the Chorten are circular, and decorated with lotus-petal designs. Seven heaped lotus steps are constructed occasionally. This refers to the seven first steps of the Buddha.

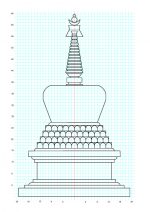

(2) Stupa of Awakening (Enlightenment) or the Conquest of Mara

(2) Stupa of Awakening (Enlightenment) or the Conquest of Mara

Commemorates the Buddha’s defeat of Mara, and his awakeningt under the bodhi tree at Bodhgaya.

This enlightenment Chorten is also known as the Chorten of the conquest of Mara. It symbolises the 35 year old Buddha’s attainment of enlightenment in the village of Magadha in Bodhgaya under the Bodhi tree on the 15th day of the 4thmonth in the Bhutanese calendar.

It is here that the Buddha subdued all the evils and conquest worldly temptations and attacks manifesting in the form of Mara.

(3) Stupa of Many Doors or Gates

(3) Stupa of Many Doors or Gates

Commemorates the Buddha’s first turning of the Wheel of Dharma in the Deer Park at Sarnath near Varanasi.

The Chorten of many Doors

The Chorten of many Doors is also known as the Chorten of many gates. After attaining enlightenment, the Buddha taught his first students in a deer park near Sarnath in Varanasi on the 4th day of the Sixth Bhutanese month.

The series of doors on each side of the steps represent the first teachings of the Buddha- the four noble truths, the six perfections and the noble eightfold path.

(4) Stupa of Miracles

(4) Stupa of Miracles

Commemorates the Buddha’s miraculous defeat of the non-Buddhists (tirthika) in the Jetvana Grove at Shravasti.

The Chorten of descent from the God Realm

At the age of 42, Buddha spent a summer retreat in Tushita Heaven, where his mother had taken rebirth. In order to repay her kindness he taught the dharma to his mother reincarnate. So in order to commemorate this event the local inhabitants built a Chorten on the 22nd day of the 9th Bhutanese month.

This stupa is characterised with a central projection at each side containing a triple ladder or steps.

(5) Stupa of Descent from the God Realm

(5) Stupa of Descent from the God Realm

Commemorates the summer retreat that the Buddha spent teaching the reincarnation of his mother in the heavenly realm of Tushita, and his descent from this realm at the city of Sankasya.

The Chorten of great miracles

This Chorten refers to various miracles performed by the Buddha when he was 50 years old. Legend claims that he overpowered Maras and heretics by engaging them in intellectual arguments and also by performing miracles.

This Chorten was raised by the Lichavi Kingdom to commemorate the event.

(6) Stupa of Reconciliation

(6) Stupa of Reconciliation

Commemorates the Buddha’s reconciliation of the disputing factions within the Sangha at Veluvana bamboo grove at Rajagriha.

The Chorten of reconciliation

According to Lam Neten of Wangduephodrang this Chorten commemorated the Buddha’s resolution of a dispute among the Sanga or among the Buddhist community.

“A Chorten in this design was built in the kingdom of Magadha, where the reconciliation occurred.

It has four octagonal steps with equal sides.”

(7) Stupa of Complete Victory

(7) Stupa of Complete Victory

Commemorates the Buddha’s prolonging of his life by three months at the city of Vaisali, when he was 80 years of age.

The Chorten of complete victory

When the Buddha was 80 years old, on the request of the king of the evils Buddha decided to attain the state of Parinirvana. But the devotees again requested the Buddha to still stay alive.

So, the Buddha then prolonged his life by three months.

In order to commemorate the prolonged life of Buddha this Chorten of complete victory was built.

It has only three steps, which are circular and unadorned.

(8) Stupa of Parinirvana

(8) Stupa of Parinirvana

Commemorates the Buddha’s passing away beyond sorrow between two sal trees at the city of Kushinigara.

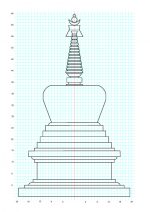

The common elements of these eight types of stupas are the foundation up to the lion throne, and the upper part from the rings upward. The middle section is where the different forms are realized.

This Chorten refers to the death of the Buddha, when he was 80 years old. It symbolises the Buddha’s complete absorption in to the highest state of mind.

It is bell shaped and usually not ornamented.

The Lam Neten of Wangduephodrang said that building a Chorten is considered extremely beneficial leaving very positive and accumulating merits in one’s life. “At times we should circumambulate the stupa with the inner thought of the teachings of the great masters,” he said.

Buddhists believe destroying or vandalising a stupa on the other hand is considered an extremely negative deed. According to the Lam Neten, such an action is believed to create massive negative karmic imprints leading to the massive future problems during the present stay and even after death.

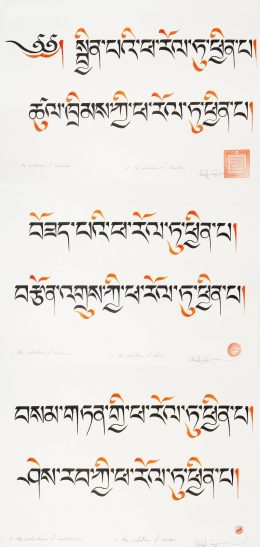

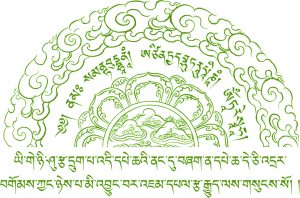

There are five mantras that Lama Zopa Rinpoche says should go in all statues and stupas. Mantras should always be rolled starting from the beginning of the mantra with the words rolled inside. Once rolled, one should draw an arrow on the outside of the roll indicating which side is up. Always place the mantras right side up inside the stupa or statue. If the statue or stupa is very small, then you can roll all five mantras together so they will all fitinside. Alternatively, you can make rolls of each of the five individually and put them inside in any order. If one has also the set of mantras called de.nga, the five powerful mantras, one can also put some of these inside, though the main portion of mantras placed inside should consist of the five mantras below.

The five mantras are:

(1) Stainless Beam root mantra, (2) Stainless Beam mantra, (3) the Most Precious Mantra Ornament of Enlightenment, (4) the Most Precious Mantra of the Secret Relic, and (5) Stainless Pinnacle mantra.

Regarding the tsog.shing mantra at the bottom of this page, this is to be written in gold in the four directions on the central pole (life tree) of large statues and stupas.

Regarding the Stainless Beam mantra, Lama Zopa Rinpoche says that if you offer a bell to a stupa that contains this mantra, the sound of the bell will purify the ten non-virtues and the five uninterrupted negative karmas of all who hear it. Also, if one circumambulates a stupa or statue that contains this mantra, it will also purify the ten non-virtues and the five uninterrupted negative karmas.

Regarding the Most Precious Mantra Ornament of Enlightenment, by putting this inside one receives the benefit of building 100,000 stupas.

Regarding the Most Precious Mantra of the Secret Relic, if one circumambulates a stupa that contains even one of these mantras, it will purify the causes ofthe eight hot hells.

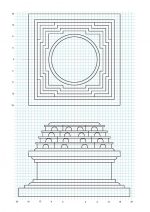

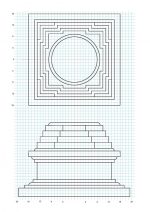

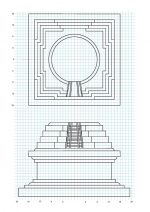

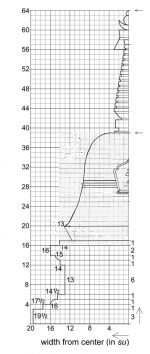

THE TWENTY-FOUR ELEMENTS OF A STUPA

|

For our purposes let’s label 4 sections:

|

FILLING A STUPA

1. The throne:

should be filled with the “wordly” substances and ojects, not mantras or statues or texts etc. You can place 4 vases in the throne –

i) treasure vase containing gold, silver, pearls, turquoise, conch shells and other jewels and semi-precious stones etc.

ii) grains vase containing wheat, barley, rice, yellow peas and unhusked rice

iii) medicinal vase containing (Tib.) le tre, gyatso luwa, kanda kari (half caterpillar, half fungus), lagpa wangpo and shudag karpo

iv) aromatics vase containing red and white sandalwoods, camphor saffron, nutmeg

Other items are new clothing, weapons, knives, cars, globe of the world, honey, butter, sugar, tea, meat, five coloured cloths (signifying the five wisdoms), magazines, pictures of masses of people, pictures of famous, influential people, pictures of rich people, soil etc. from holy places. If there is much space then it can be filled with more grains and other foodstuffs (sealed off from insects), and incense and aromatic wood etc. The Dzambala mandala should go in the throne under the sog.shing.

2. The sog.shing (life-tree or life-wood) goes through the centre of the stupa from the base of the steps (bang rim) up to the top of the 13 rings.

3. The 4 steps and vase:

filled with Dharma objects such as tsatsas and statues, mantras, texts, relics. Imagining that a buddha is sitting inside the stupa with the head touching the top of the vase and the legs crossed at the base of the 4 steps, the various statues, mantra rolls texts and relics should be placed at the appropriate level. The largest number of mantras should be the 4 Dharmakaya Relic mantras which can be placed anywhere.

This is advice given directly by Lama Zopa Rinpoche regarding stupas –

The two garlands on either side of the 13 rings should not be regarded as optional, as decorations. They have significance as they symbolize the 2 truths.

Dec 26, 2011 Once a stupa has been consecrated there should not be any structural work done on the body of the stupa, such as drilling, chipping or modifying. Adding things, like paint, decorations, is OK. If renovation work has to be done there is a special process for temorarily “storing” the transcendental wisdom invoked during the consecration.

Jan 7, 2011 “All stupas have 4 levels, it signifies the 4 mindfulness’s of the 37 wings to Enlightenment. Rinpoche said he has seen stupas with 3 levels but better to keep to 4 as it has significance.”

Contents of Stupa

This Stupa of great liberation through eye sight will contain the following texts and statues:

Le mandala “eu sel drimé ki”

The mandala “eu sel drimé ki” comprises:

All statues will be bought in Nepal, all texts will come from the Tibetan printers of Delhi.

Seat of the mind touk ten

Kadampas stupas, and the eight noble stupas, two-feet tall.

In total, 108 stupas will come from Nepal. The global budget for the seats of body, speech and mind has been included in the estimate provided by the architect.

1. The reason why there is a Tree of Life inside stupas and statues, is because it represents our central channel or nadi, as explained by Dordrak rigdzin chenpo Péma Trinlé in the text “Mirror of Sapphire”.

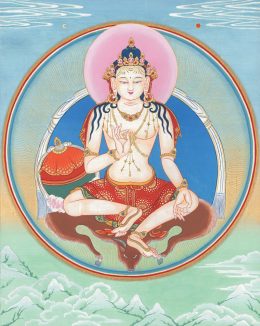

2. In front of the Tree of Life stands the wheel “tsok dak langpo”, as illustrated below. It is an emanation of the great being of compassion Avalokiteshvra and the source of all wealth. This wheel will be made of red copper and will be 2.5 feet wide.

3. Around each mandala, 7 traditional silver offering bowls, a silver vase, a silver offering mandala, a silver butter lamp, a vajra, a bell, a damaru, a silver serkyem for offerings to Mahakala, and a kapala. In all four directions, all these offerings will be present.

4. Around the vase of the stupa, the following offerings will be made in the four directions: the 8 auspicious signs, the 8 auspicious substances, the 7 possessions of the universal monarch, the 5 objects of pleasure, the 7 types of jewels. All these offerings will be made in copper.

5. Sound offerings: various cymbals, drums, gyaling, large horns, conchs, and small cymbals, all in the four directions.

6. In the center of the vase, the mandala “tsouk tor drimé ki” will stand, as illustrated below:

7. The base of the vase will comprise the following wheels neu djin po khor mo khor. The reason is that, through blessings of the Seats of Body and Mind, the suffering in all countries due to poverty, hunger and thirst will be dispelled. Thus, all beings will experience joy, happiness, and prosperity. These two-feet-wide wheels will be in copper.

The total amount for the seats of body and mind has been included in the architect’s estimate.

1. First of all, above the vase, thirteen levels and the summit will be in copper covered by gold, to 11.26 meters height.

Vajrakila

2. In the cavity of the vase, a 3-meter-high Vajrakila statue will be placed as below, made from clay, mendroup and precious medicinal substances.

3. In this stupa of great liberation through eye sight, there will be 3 temples. The temples (A,B,C) shall comprise the following statues:

A

A. In the first temple, a 2-meters-high statue of thousand-arms Avalokiteshvara will be placed, surrounded by the 8 noble Boddhisttvas, 1.5-meter, all made from clay, men droup and precious medicinal substances.

B

B

B. In the second temple, a Sakyamuni Buddha statue, 3.5-meter-high, surrounded by 1.5-meter Shariputra and Mauglayana on the the right, 2-meters Longchenpa and Pema Lingpa on the left, all made from clay, men droup and precious medicinal substances.

C

C. In the third temple, a 2.5 meter Gourou nang sid sil neu surrounded by 1.5-meter Yeshe Tsogyal and Mandarava on the right, 2-meter Guru drakpo and Dorjé Drolo on the left, all made from clay, mendroup and precious medicinal substances.

The total amount for the 13 levels of the summit, all statues, substances contents and paintings of frescoes, has been included in the architect’s estimate. .

In all 8 stupas, the following texts and statues will be placed:

Seat of the Mind touk ten

In each stupa, there will be a kadampa stupa, 3000 tsa-tsa, mandalas, a Tree of Life, offerings, a wheel tsok dak langpo, a wheel neu djin po khor mo khor and offerings as in the large stupa.

The total amount for the seats of body, speech and mind has been included in the architect’s estimate.

Khatvanga

Khatvanga (Skt. khatvanga ; Tib. ཁ་ཊྭཱཾ་ག་, Wyl. kha Twan ga) — um tridente com elementos simbolicos.

Khatvanga (Skt. khatvanga ; Tib. ཁ་ཊྭཱཾ་ག་, Wyl. kha Twan ga) — um tridente com elementos simbolicos.

A Atitude do Vagabundo – Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche diz:

-

- O khatvanga é um objeto bastante bonito, que se parece com uma bengala com três dentes apontadores para cima. Uma explicação da khatvanga é muito difícil. Basta dizer que o kapala (skull-cup) e o khatvanga (tridente) são considerados duas das maiores substâncias na vajrayana, especialmente se você é um dos praticantes mais vajrayana.

- Em um sentido metafórico, o khatvanga também é um atributo de um vagabundo. Ele simboliza a prática de um vagabundo: uma prática tântrica em que o mundo é sempre visto como um mundo estranho, como se fosse um lugar nunca antes encontrado. É como se fosse a sua primeira vez a visitar esta terra. Em suma, ter a atitude de um vagabundo também é semelhante a ser alguém sem comida, sem tapete, sem uma revista Lonely Planet na sua bolsa, muito menos cartões de crédito, ou um telefone celular para ligar para casa. E, como praticantes tântricos, é muito importante que você sempre tente desenvolver a atitude de um vagabundo ao olhar para o mundo. [1]

Simbolismo externo

O vajra cruzado representa a terra que forma a base do mandala do Monte Meru. O vaso com seus quatro pingentes em forma de folha representa Monte Meru e suas quatro faces. A cabeça recém-cortada acima dela (de cor vermelha) representa os seis céus dos deuses do reino do desejo (kamaloka). A cabeça cortada em decúbito acima (cor azul ou verde) representa os dezoito céus do reino da forma (rupaloka). A cabeça em decomposição indica a morte do desejo nos deuses que permanecem nesses céus. O crânio sem carne acima (cor branca) representa os quatro céus do reino sem forma (arupaloka). A ausência de carne indica a morte do desejo e do ódio nesses deuses. O tridente, trishula, representa as Três Jóias e os Budas do passado, presente e futuro. O damaru e o sino pendurados representam a união de meios hábeis e sabedoria. O pingente, laço de três cores simboliza a bandeira da vitória colocada no pico do Monte Sumeru. O lenço branco, khatag, pendurado amarrado ao vaso representa a montanha e o grande oceano salgado que circunda Mount Sumeru.

Simbolismo interno

O vajra cruzado simboliza os quatro elementos purificados de terra, água, fogo e ar; as quatro atividades (karmas); e as quatro portas da libertação (vazio, insensibilidade, falta de desejo e falta de composição). O vaso representa a consciência não conceitual da mente como a perfeição do “néctar de conquista” da sabedoria. A cabeça recém-cortada simboliza o nirmanakaya e o vazio da causa. A cabeça em decomposição simboliza o sambhogakaya e o vazio do efeito. O crânio completamente exposto simboliza o dharmakaya e o vazio dos fenômenos. O tridente representa os três canais, com as chamas ao redor do dente central simbolizando a ascensão do fogo interno do tummo (gtum mo). O significado do damaru e do sino suspensos permanece inalterado, enquanto a fita de três cores indica os três veículos: Hinayana (amarelo), Mahayana (vermelho) e Vajrayana (azul). O lenço branco pendurado simboliza os ensinamentos de todas as nove yanas.

Referências:

- Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche , Manual Longchen Nyingtik , Fundação Khyentse, 2004, página 97.

- Robert Beer, a enciclopédia de símbolos e motivos tibetanos , Shambhala, 1999, página 252.

- http://www.rigpawiki.org/index.php?title=Khatvanga

Dutsi

Dutsi ou Amrita (tibetano: bDud.rTsi) é, no budismo Vajrayana, uma bebida sacramental que é consumida no início de todos os rituais importantes, por exemplo, abhisheka/iniciação e ganachakra/tsog). É o néctar de bênçãos. Na tradição tibetana, o dutsi é feito durante o drubchen. Geralmente, toma a forma de pequenos grãos castanhos escuros que são tomados com água, ou dissolvidos em soluções muito fracas de álcool, e é dito que melhora o bem-estar físico e espiritual.

Dutsi ou Amrita (tibetano: bDud.rTsi) é, no budismo Vajrayana, uma bebida sacramental que é consumida no início de todos os rituais importantes, por exemplo, abhisheka/iniciação e ganachakra/tsog). É o néctar de bênçãos. Na tradição tibetana, o dutsi é feito durante o drubchen. Geralmente, toma a forma de pequenos grãos castanhos escuros que são tomados com água, ou dissolvidos em soluções muito fracas de álcool, e é dito que melhora o bem-estar físico e espiritual.

Referência: http://www.chinabuddhismencyclopedia.com/

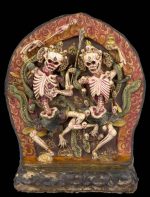

Citipati

Citipati (Shmashana Adhipati – དུར་ཁྲོད་བདག་པོའི་ཡབ་ཡུམ། སྲུང་མ།)

Citipati (Shmashana Adhipati – དུར་ཁྲོད་བདག་པོའི་ཡབ་ཡུམ། སྲུང་མ།)

Chitipati são o Rei e Rainha dos Cemitérios.

De acordo com a lenda budista Citipati foram dois ascetas em sua vida anterior. Uma vez eles estavam em meditação tão profunda, que não perceberam um ladrão que acabou cortando suas próprias cabeças. Eles se tornaram inimigos ferozes desse ladrão e juraram vingança eterna.

Citipati são considerados divindades protetoras importantes.

Eles geralmente são retratados como dois esqueletos, um masculino e outro feminino. O Citipati é uma das 75 formas de Mahakala e são lembretes visíveis da impermanência de tudo que é mundano.

Eles são protetores especiais de Chakrasamvara e da Dakini Vajrayogini.

Cada um detém um cetro especial, feito de uma cabeça morta com a coluna vertebral ainda anexada à sua direita e uma tigela de crânio, kapala, de sangue contendo cérebro na mão esquerda, enquanto está na perna esquerda um topo uma concha. Suas bocas são separadas em um grande sorriso, mostrando todos os dentes. As figuras estão em posição de dança com as pernas entrelaçadas de pé em um disco de sol vermelho em um trono de lótus. Eles estão rodeados pelas chamas vermelhas da consciência prístina.

No cemitério, o Citipati deve realizar uma dança ritual de durante a qual eles sopram os long horn tibetanos. Na maioria dos mosteiros, a dança, simbólica do ciclo da vida e da morte, é formada no cemitério do mosteiro uma vez no verão e uma vez no inverno, por monges usando máscaras.

As formas esqueléticas são chamadas de Shri Chitipati e são Seres Divinos, cuja função principal pode ser considerada a tutela dos “funerais celestiais”, muitas vezes referidos como os Gloriosos Senhores da Pira (de cremação). Quase a totalidade da população budista na de todos os tempos históricos foi cremada.

O Shri Chitipati é sempre mostrado na forma esquelética e geralmente é considerado um Pai com uma Mãe, embora outras teorias sejam abundantes. Todas as cabeças de Shri Chitipati sejam mostradas com um “terceiro olho de sabedoria e iluminação”. Eles são descritos dançando sobre

conchas (que são o símbolo tibetano da música) e abraçados. Outras constantes nas poucas esculturas e representação deste tipo conhecido incluem o uso de coroas com cinco crânios e um Jin Chang Chu (uma arma antiga da Índia adotada para simbolicamente representar o instrumento ritual que destroi os demônios), que fica no topo da coroa. O Shri Chitipati também detém uma vara esquelética em uma mão que simboliza a capacidade de esmagar a causa de maus atos, fala e pensamentos ruins. O Pai segura em uma mão uma tigela que simboliza ter tomado o controle do sangue da negatividade. Sua Mãe segura um vaso com o “doce orvalho da sabedoria ” na mão direita, e uma “flor/grão” protetora na mão esquerda.

Referencia: Jimmy´s Art Gallery e http://www.chinabuddhismencyclopedia.com/

Kshitigarbha

Kshitigarbha é um dos quatro principais bodhisattvas no budismo Mahayana. Os outros são Samantabhadri, Manjushri e Avalokiteshvara.

Kshitigarbha é um dos quatro principais bodhisattvas no budismo Mahayana. Os outros são Samantabhadri, Manjushri e Avalokiteshvara.

Kshitigarbha fez o voto de não alcançar o estado Búdico até que todos os infernos estejam esvaziados. Ele é, portanto, muitas vezes considerado como o bodhisattva dos seres do inferno, bem como o guardião das crianças e a divindade patronal de crianças falecidas e fetos abortados na cultura japonesa, onde é conhecido como Jizo ou Ojizo-sama, o protetor de crianças.

Referencia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kshitigarbha

Cores Na Cultura Tibetana

O budismo tibetano é considerado uma forma extravagante de uma religião tradicionalmente simples, com sua arte e rituais elaborados, repleto de cores vivas.

O budismo tibetano é considerado uma forma extravagante de uma religião tradicionalmente simples, com sua arte e rituais elaborados, repleto de cores vivas.

Todas as cores usadas na arte tibetana e seus rituais possuem significados específicos.

Existem cinco cores principais que são conhecidas como pancha-varna em sânscrito, o que significa Os Cinco Luzes Puras, de acordo com a cultura tibetana. Cada cor representa um estado de espírito, um Buda, uma parte do corpo, uma parte da palavra mantra Hung ou um elemento natural.

Diferentes cores no budismo tibetano

O azul está associado à pureza e à cura. Akshobhya é o Buda com essa cor. As orelhas são a parte do corpo que é representada pela cor azul. O ar é o elemento que acompanha essa cor. Acredita-se, ao meditar sobre essa cor, a raiva pode ser transformada em sabedoria.

O branco é a cor da aprendizagem e do conhecimento no budismo. É representado pelo Buda Vairocana. Os olhos estão associados com o branco. No branco está no elemento água. Se meditamos, o branco pode cortar a ilusão da ignorância e transformá-la na sabedoria da realidade.

O vermelho está relacionado à força vital e à preservação. O Buda Amitabha é retratado com um corpo vermelho na arte tibetana. A parte do corpo associada a esta cor é a língua. O fogo é o elemento natural complementar à cor vermelha. No budismo, meditar na cor vermelha transforma a ilusão do apego na sabedoria do discernimento.

O verde é a cor do equilíbrio e da harmonia. Amoghasiddhi é o Buda da cor verde. A cabeça é a parte do corpo associada a esta cor. O verde representa a natureza. Medite nessa cor para transformar o ciúme na sabedoria da realização.

O amarelo simboliza o desapego e a renúncia. Buddha Ratnasambhava está associado com o amarelo. O nariz é representado por esta cor. A terra é o elemento que acompanha a cor amarela. O amarelo transforma o orgulho em sabedoria de equanime quando visualizado na meditação.

Estas Cinco Luzes Puras são muitas vezes vistas em Mandalas e bandeiras de oração budistas tibetanas e pedras mani no topo das montanhas.

Simbolismo de cores no budismo tibetano

Acredita-se que, meditando sobre as cores individuais, que contêm suas respectivas essências e estão associadas a um Buda ou Bodhisattva particular, as transformações espirituais são alcançadas.

As bandeiras de oração coloridas são uma visão única e freqüentemente vista nas regiões autônomas do Tibete na China e países vizinhos como Nepal, Butão e Caxemira, etc. Nestas bandeiras estão os mantras budistas tibetanos densamente inscritos, a imagem de Budas tibetanos e criaturas ou deuses auspiciosos.

Como um objeto simbólico para espalhar a boa sorte, a paz, a simpatia e a sabedoria para os seres humanos, as bandeiras de oração têm um padrão de cor fixo e uma ordem que não devem ser alteradas aleatoriamente. E, normalmente, uma série de bandeiras de oração consiste de 5 cores:

No topo é uma bandeira azul, que simboliza o céu azul; Em seguida vem bandeira branca e representa nuvens brancas; A seguir a bandeira branca é a bandeira vermelha e é a cor da chama; O último mas o verde é verde e mostra o rio verde; O fundo é amarelo, o que representa a terra. Essas 5 cores refletem os 5 fenômenos naturais do nosso mundo e cada um está intimamente conectado e indispensável. Até certo ponto, também mostra o anseio dos tibetanos por uma vida pacífica e feliz.

Por que o vermelho e o amarelo são preferidos no budismo tibetano:

Viajando no Tibete, dificilmente pode encontrar cores vermelhas e amarelas para ornamentos de casas comuns dos tibetanos. Enquanto visitam os mosteiros tibetanos, essas duas cores são amplamente utilizadas e os vermelhos ou amarelos também são considerados ortodoxos para a roupa das monges tibetanas.

Uma série de templos amarelos, convidados ou salões de meditação também podem ser encontrados no Tibete. A arquitetura amarela mais antiga remonta ao “Buzi Golden Palace”, construído por Songtsen Gampo no Mosteiro de Samye. Tem sido uma tradição que apenas os prestigiosos mosteiros ou residências de monges eminentes podem ser revestidos de cor amarela. Portanto, você pode encontrar amarelo no salão Qangba Buddha no Drepung Monastery, edifício principal do Mosteiro Mindrolling, etc.

Dicas: Para as pessoas comuns, sua casa é pintada de branco para expressar sua reverência pela santidade dos deuses, bem como uma maneira eficaz de evitar a radiação ultravioleta forte no planalto.

O significado da cor do arco-íris no budismo tibetano

O significado da cor do arco-íris no budismo tibetano

Além do simbolismo das cores individualmente, há o conceito budista do “corpo de arco-íris”. O corpo do arco-íris é um conceito no budismo tibetano quando tudo começa a se transformar em luz pura. É dito ser o estado mais elevado alcançável no reino de Samsara antes da “luz clara” do Nirvana.

À medida que o espectro contém em si todas as manifestações possíveis de luz e, portanto, de cor, o corpo do arco-íris significa o despertar do eu interior para o espaço completo de conhecimento terrestre que é possível acessar antes de passar pelo limiar para o estado do Nirvana. Compreensivelmente, quando representado nas artes visuais, devido à profusão de cores, o resultado é espetacularmente único.

Referências: http://www.tibettravel.org/tibetan-buddhism/meanings-of-colors-in-tibet.html

Bandeira do Tibet

Bandeira do Tibete

Bandeira do Tibete

CONTEXTO HISTÓRICO1

Durante o reinado do rei do século sétimo, Songtsen Gampo, o Tibete foi um dos impérios mais poderosos da Ásia Central. O Tibete, então, tinha um exército de 2.860.000 homens. Cada regimento do exército tinha sua própria bandeira.

Esta tradição continuou até que o Décimo terceiro Dalai Lama projetou uma nova bandeira e emitiu uma proclamação para sua adoção por todos os estabelecimentos militares. Esta bandeira tornou-se a atual bandeira nacional tibetana.

O simbolismo da bandeira nacional tibetana:

- No centro fica uma magnífica montanha coberta de neve, que representa a grande nação do Tibete, amplamente conhecida como a Terra cercada por montanhas da neve.

- As seis bandas vermelhas espalhadas pelo céu azul escuro representam os antepassados originais do povo tibetano: as seis tribos chamaram Se, Mu, Dong, Tong, Dru e Ra, que por sua vez deu origem aos (doze) descendentes. A combinação de seis bandas vermelhas (para as tribos) e seis bandas de azul escuro (para o céu) representa a promulgação incessante das ações virtuosas de proteção dos ensinamentos espirituais e tradição pelas divindades protetoras guardiões preto e vermelho com as quais o Tibete tem foi conectado desde tempos imemoriais, as duas divindades guardiãs conhecidas como MAR NAG NYIE.

- No topo da montanha nevada, o sol com seus raios brilhando em todas as direções representando o gozo equanime da liberdade, felicidade espiritual e material e prosperidade por todos os seres na terra do Tibete.

- Nas encostas da montanha, um par de leões de neve permanece orgulhosamente, ardendo com chamas de destemor, que representam a realização vitoriosa do país com uma vida espiritual e governamental unificada.

- A bela e radiante jóia de três cores mantida no alto representa a sempre presente reverência e respeito guardadas pelo povo tibetano em relação às três jóias supremas, os objetos de refúgio: Buda, Dharma e Sangha.

- A jóia com dois redemoinhos coloridos entre os dois leões representao valor e o cuidade mantido pelo povo, a autodisciplina do comportamento ético correto, representado principalmente pelas exaltação da pratica das dez virtudes e dos 16 modos de conduta humana.

- O adorno com uma borda amarela de três lados: o florescimento dos ensinamentos do Buda, que são como ouro puro e refinado e sem limites no espaço e no tempo.

- A borda branca significa a abertura das fronteiras: a abertura do Tibete ao pensamento não-budista.

Referências

Garab Dorje

Garab Dorje (T): Sanskrit: Pramodavajra, Prahevajra, Surati Vajra. Indian yogin and tantric adept who lived somewhere between 184 BCE and 57 CE. His life story is full of miraculous events and powers, yet Tibetans regard him as an historical figure, who like Padmasambhava, was born in Oddiyana from the virgin womb of a royal nun. He is generally regarded as the first human teacher of Dzogchen. As a nirmanakaya-emanation of the Buddha Vajrasattva, Garab Dorje received all the 6.4 million tantras and oral instructions of Dzogchen directly from the heavenly realm and thus became the first human vidyadhara (Skt., Knowledge Holder/T. rig-dzin) in the Dzogchen lineage. Having reached the state of complete enlightenment, he then transmitted these teachings to a retinue of exceptional beings, among who was Master Manjushrimitra, one of the greatest debaters of his day, who is regarded as the chief student of Garab Dorje who in turn passed them on to Sri Singha. Centuries later, Padmasambhava and Vairocana received the transmission of the Dzogchen tantras through Garab Dorje’s wisdom form; i.e. through a pure vision on Lake Dhanakosa in Oddiyana. Garab Dorje composed the “Natural Freedom of Ordinary Characteristics” and the “three words that strike the essence” his last testament in the form of three essential points given to Manjushrimitra; summing up the teachings of Dzogchen: a direct introduction to one’s own nature, deciding that there is nothing other than this and the capacity to abide in this unique state with confidence in liberation.

Cintamani - Meditação e Arte - Copyright 2020 - Todos os direitos reservados.

Cintamani - Meditação e Arte - Copyright 2020 - Todos os direitos reservados.