Documentos

Projeto Roda de Oração – Em Memória de Israel “Tchushin” Felix

Projeto Roda de Oração – Em Memória de Israel “Tchushin” Felix

O Projeto foi idealizado segundo a aspiração de um praticante da Sangha de Florianópolis, Sr. Israel Felix, que o Dawa o apelidou de Israel Tchushin, por causa do cajado que ele usa o qual tem um Tchushin (Dragão da Água) esculpido.

Ele tem dificuldades para se mover e gostaria de ter uma roda de oração em casa para praticar em sua sala.

A encomenda foi de uma roda de oração cuja a base fosse 50cm (quadrada).

A partir dessa medida estabelecemos o tamanho da roda que giraria em cima desta base.

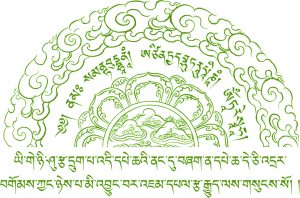

Com isso podemos diagramar o tamanho das fontes do mantra que cobre todo o perímetro da roda, as pemas (flores) e timbas (núvens).

OM MANI PADME HUNG

Pema e Timba

A Roda foi feita em madeira maciça de canela com o firo no centro. O rolo foi torneado e os encraves feitos deixando a parte onde será esculpida o mantra e pintados as pemas e timbas.

Folhas de Mantras

Os mantras foram feitos conforme o desejo do Sr. Israel Tchuchin:

Vajra Guru, Buda da Medicina, Vajrakilaya, Cherenzig e Tara, totalizando 200.000 mantras mais as dedicações adequadas. Todo o processo de impressão e enrolar dos mantras foram feitos conforme a tradição e sob a orientação de Lama Rigdzin Sandup e com a ajuda de Mauriã.

Os mantras são alinhados e colados folha a folha em linha, isto é, em cada folha há um pouco de cada mantra como se eles fosse recitados todos um de cada vez e no final de cada linha há a dedicação e preces adequados.

Com o rolo pronto e bem alinhado, as bordas são pintadas e o rolo é colocado no eixo da roda.

O Telhado tem várias linhas que precisam ser feitas, não fazê-las é como não virtude.

• Timba

• Pema

• Gud-ga

• Tchutcha

• Pema

Com a parte em madeira pronta, podemos começar a pintura: as bases são pintadas. Neste ponto ficou tudo muito extranho, pois perdeu a forma lisa da madeira e parecia mesmo uma bagunça.

Com a parte em madeira pronta, podemos começar a pintura: as bases são pintadas. Neste ponto ficou tudo muito extranho, pois perdeu a forma lisa da madeira e parecia mesmo uma bagunça.

Fizemos Stencil para acelerar o processo das pinturas que não tem shadow.

Neste ponto a coisa começo a tom ar forma e já dava par vislumbrar algo “tibetano” na pintura.

ar forma e já dava par vislumbrar algo “tibetano” na pintura.

A Lachimi estava adorando toda aquela bagunça na varanda e estava difícil manter ela longe das tintas.

As tardes estavam tão lindas naquela época que dava gosto de ajudar… era um  clima meio nostálgico que parecia somar com a delicadeza dos cuidados com os traços. Foram horas que valiam a pena.

clima meio nostálgico que parecia somar com a delicadeza dos cuidados com os traços. Foram horas que valiam a pena.

Logo esfriou e o trabalho ficou mais difícil, pois as partes superiores, e o teto também tem o mesmo desenho das partes da frente. As vezes tínhamos que deitar mesmo a roda para que fosse possível pintar.

Logo esfriou e o trabalho ficou mais difícil, pois as partes superiores, e o teto também tem o mesmo desenho das partes da frente. As vezes tínhamos que deitar mesmo a roda para que fosse possível pintar.

E foi tomando forma…

Mais uns dias e muitas mão de tinta e estava uma gracinha:

Quanto ficou pronta a pintura da Rin-ha, nem dava para acreditar que aquilo tinha sido feito aqui, estava perfeito, exatamente como tinha que ser.

Com a pintura da “casinha” pronta, podemos fixar a roda nos rolamentos.

Daí a coisa complicada foi ensinar a  Lachimi para que lado a roda tem que girar… também aproveitamos para ensiná-la a recitar o mantra… que acabou ficando “mani mani mani”…. mas a intenção é que vale.

Lachimi para que lado a roda tem que girar… também aproveitamos para ensiná-la a recitar o mantra… que acabou ficando “mani mani mani”…. mas a intenção é que vale.

Agora o Telhado foiçou dourado e os ornamentos fixados:

• Sertok, que representa implementos budistas: jóia, vaso de longa vida, sino e pema.

• Pema e Timba

• Pema e Timba

• Patha

Quando achamos que a roda estava pronta,  Dawa passou algumas horas tentando fazer a Lachimi girar a roda para o lado certo e recitar mantras.

Dawa passou algumas horas tentando fazer a Lachimi girar a roda para o lado certo e recitar mantras.

Quando a Roda estava pronta para embarcar na transportadora, Sr. Israel Tchuchin esteve no interior do templo e começo a ter idéias:

Viu vários ornamentos e pediu para adicionar na pintura da casinha, no ornamento do entorno do teto e nos pilares. Realmente eles somaram, mas já se foram mais 3 mêses de um total de 8 meses.

O resultado foi inesperado.

Eu não sabia que o Dawa sabia pintar tão bem!

A parte em madeira eu tinha completa certeza do conhecimento e capacidade do Dawa, mas o que foi feito na pintura me surpreendeu.

No final a roda ficou com 72cm de lado pois o Dawa imaginou que o Sr. Israel soubesse da necessidade do telhado.

Sr. Israel também se assustou um pouco com o tamanho, mas gostou tanto do trabalho que colocou no centro de sua sala. Já me disseram que o apartamento dele é um pouco pequeno… acho que ele deve ficar longas horas girando os mantras.

Além da sensação de dever cumprido ficou aquele gostinho de trabalho bem feito, de superação.

Que os méritos gerados possam beneficiar a muitos seres.

Em memória de nosso amigo e incentivador, Israel “Tchushin”

Que, devido a nossa aspiração de beneficiar a muitos seres, possamos nos reencontrar em muitos renascimentos.

Dechen

Dzi

To Tibetans and other Himalayan people, the dZi is a “precious jewel of supernatural orign” with great power to protect its wearer from disaster. The Tibetan people believe dZi beads are spiritual stones fallen from Heaven which bring good karma to those who own them. The ancient Dzi absorbs cosmic energy from the universe. Tibetans generally believe that dZi beads are of divine origin and therefore not created by human hands. Some say they are dropped by the Gods to benefit those who have the good fortune to find them. Since they are believed to have a divine source, they are considered to be a very precious and powerful amulet. Beads can often be seen in Tibetan temples adorning the most revered statues and sacred relics. They are thought to bring good fortune, ward off evil, and protect the wearer from physical harm and illness. It has even been claimed by Tibetan refugees, that they protect the wearer from knife and bullet attacks!

- Tibet Map

Dzi (pronounced Zee) is a Tibetan word used to describe a patterned, usually agate, of mainly oblong, round, cylindrical or tabular shape pierced lengthwise called Heaven’s Bead (tian zhu) in Chinese. The meaning of the Tibetan word “Dzi” translates to “shine, brightness, clearness, splendour”. The beads originate in the Tibetan cultural sphere and can command high prices and are difficult to come by. It’s said to possess mysterious powers and bring good fortune to the wearer. Ancient and pure dZi beads of Tibet are extremely precious and rare. No matter how many or how few eyes they bear, all dZi beads possess the mystic power of bringing luck, warding off evil, stabilizing blood pressure, guarding against apoplexy and enhancing body strength. Owners and wearers of these beads are blessed with unexpected credit, luck and perfection They are found primarily in Tibet, but also in neighbouring Bhutan, Ladakh and Sikkim. Shepherds and farmers pick them up in the grasslands or while cultivating fields. Because dZi are found in the earth, Tibetans cannot conceive of them as man-made. Since knowledge of the bead is derived from oral traditions, few beads have provoked more controversy concerning their source, method of manufacture and even precise definition. This all contributes to making them the most sought after and collectable beads on earth. The most prized pure dZi, are generally beads with eyes or unusual decorations. A pure dZi may or may not have eyes. It can be opaque or partially translucent (In Tibet, translucent beads are usually valued lower). The most sought after base colour is an opaque dark brown to black.

This is an authentic old tibetan 9 eye dzi:

Reputed to be the most powerful and prized of all Dzi beads, a 9-eyed Dzi is believed to be able to gather the Nine-Fold Merits & bring immense benefits & the most complete blessings. It helps gain power, glory, influence, fame & reputation. 9-eyed Dzi bead also brings windfall & speculative luck, attracts good fortune, promotes health luck, encourages growth of compassion, clears obstacles in your life journey, & offers protection against misfortunes & negativities.

About three to four thousand years ago, a meteor from Mars crashed into the Himalayas. This led to the 14 different types of Mars elements in Dzi beads, with the element ytterbium possessing the strongest magnetic field. This is what gave rise to the mystic power of Dzi beads. Wearing Dzi beads in the long run can enhance our blood circulation and metabolism. It also improves our quality of sleep, revitalizes our body and balances foreign magnetic fields which may be harmful to us.

Patterns on Dzi beads reflect Brahmanic teaching of ancient India, and are symbolic of the “wulunfajieta” beliefs. Each pattern bears a different meaning. Yet they are somewhat similar to the Taoist beliefs of Yin & Yang and the 5 elements as the fundamentals of life. Hence from the geomancy point of view, Dzi beads can improve one’s luck and help to ease problems and worries. The five-element system views the human body as a microcosm of the universe with the tides of energy and emotions waxing and waning. These energies and emotions are stored in the visceral organs and move through specific pathways or meridians in the body in a regular and cyclical fashion.

When these energies or emotions become blocked, or deficient or excessive through stress, trauma or disease, the five-element practitioner may use carefully controlled pressure on certain meridian points to help move the energy or emotions. This restores the natural cycle of energy and emotional movement, thus helping the person’s natural ability to heal.

There are five elements that operate to provide balance and structure to not only the world, but also our lives and bodies. These five elements are water, fire, metal, earth and wood. The philosophy behind the five elements and their use for healing purposes is that everything in the world is made up of a combination of them. Due to this interconnectivity, each and everything has certain characteristics that are linked to the elements. We can look at the body and how it ties into the elements and the way it works. The liver and the gall bladder are linked to the wood element, small intestines and the heart are connected to the fire element, spleen and the stomach to the earth, lungs and large intestine to metal and finally kidneys and bladder to the water element.

When a large portion of the bead breaks off the Dzi stone bead is seen as being finished with its work. It is time for the bead to be retired and allowed to rest as its reward for all of the work it has done. To tell whether the bead qualifies to be considered broken, check to see if any portion of the bead’s symbols, lines, eyes, etc. have been broken into. If the bead’s symbols have been broken it is considered broken. If the symbols are in tact it is considered still viable. The same applies for any crystal or gem stone. Usually the ‘broken’ stone is returned to the earth. Be grateful and give thanks for the work it has done.

Supply and demand

Due to the unknown origin and high demand of the beads, there has been unquestionable counterfeiting in Asia. Some are replicas created for decorative purposes, and accepted by the general public. In Chinese culture, a necklace is believed to be genuine if it was obtained without monetary exchange, for example from a temple. The other cultural requirement is that one should not request or bribe for it.

The pattern on the Dzi bead may not look exactly the same as in the pictures but will retain its main symbol and representation.

The Tibetan Dzi has been cleansed of negative energy, however it is suggested that

- Tibetan Dzi – 1 Eye

- Tibetan Dzi – 2 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 3 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 5 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 6 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 7 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 8 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 9 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 10 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 11 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 12 Dyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 13 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 9 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 15 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – Diamond Eye Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 17 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 18 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 19 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 20 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 81 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – 99 Eyes Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – Tiger Tooth Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – Sau Dzi – Fortune and Longevity

- Tibetan Dzi – Ruyi Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – Medicine Dzi Beads

- Tibetan Dzi – Lotus Flower Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – Lightning Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – Kuan Yin Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – Heavan and Earth Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – Garuda Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – Bat Dzi

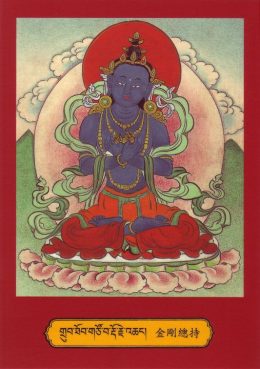

- Tibetan Dzi – Dorje Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – Bodhi Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – Bandedor Striped Dzi

- Tibetan Dzi – Diamond Eye Dzi

Mala Budista

“…mantras for ”Increasing” should be recited using malas of Bodhi seeds, gold or amber. The mantras counted on these can “serve to increase the fortune of life” such like mantra of Yellow Jambhala.(the god of wealth)…”

Dzi Bead – Coral – Âmbar

A mala is a set of beads used for counting “mantras” which are the expression of a Buddha-aspect on the level of sound. The number of mantras gets counted to ensure certain meditation results will occur.

In Tibetan Buddhism, traditionally malas of 108 beads are used. Doing one 108-bead mala counts as 100 mantra recitations; the extra repetitions are done to amend any mistakes. The materials used to make the beads can be different according to the purpose of the mantras beening used. These beads can be made from Bodhi seeds, Rudraksha seeds, lotus seeds( called ‘Moon and Stars’ by Tibetan) , sandalwood, abelia, gold, silver, copper, iron, crystal, coral, ivory, amber, coloured glaze, turquoise, giant clam, pearls and so forth, and even bones of a holy monk or revered lama.

Holy bone malas are made from the bones of mahasiddhas or lamas and hand made by highly skilled lamas, therefore, they are extremely precious. The lama who makes the holy bone mala, will chant mantras while shaping the bones into beads and polishing them. The whole process of making a holy bone mala may take over one decade, hence there goes a saying in Buddhism: holy bone malas can bring peace to the dead and safety to the living. What the holy bone mala represents, in mundane words, is that life is ever-changing and death may knock at your doors in anytime, therefore, one should be diligent in his or her practice; in Dharmata chos nyid, is the emptiness.

Cristal de Quartzo

Some beads, such as the ones made of lotus seeds, can be used for all purposes and all kinds of mantras. However, in Tibetan Buddhism, beads are recited for four different purposes:

1: Pacifying mantras should be recited using white colored malas such as crystal. These can serve to purify mind and clear away obstacles in one’s life, like illness, bad karma and mental disturbances.

2: Increasing mantras should be recited using malas of Bodhi seeds, gold or amber. The mantras counted on these kinds of mantras, for instance, mantra of Yellow Jambhala, can “serve to increase life span, knowledge and merits”.

2: Increasing mantras should be recited using malas of Bodhi seeds, gold or amber. The mantras counted on these kinds of mantras, for instance, mantra of Yellow Jambhala, can “serve to increase life span, knowledge and merits”.

3: Mantras for magnetizing are meant to tame others, but the motivation for doing so should be a pure wish to  help other sentient beings and not to benefit oneself. To do mantra of Amitayus and Kurukulle, malas made of coral should be used.

help other sentient beings and not to benefit oneself. To do mantra of Amitayus and Kurukulle, malas made of coral should be used.

4: Mantras to tame by force should be recited using malas made of bones of mahasiddhas. Reciting this kind of mantras with mala serves to tame others, but with the motivation to unselfishly help other sentient beings. To tame by force means to subdue harmful energies, such as “extremely malicious spirits, or general afflictions”. Only a person such like Dakini  that is motivated by great compassion for all beings, including those they try to tame, can do this.

that is motivated by great compassion for all beings, including those they try to tame, can do this.

Beads made of lotus seeds can be used for many purposes and for counting all kinds of mantras.

Que todos possam se beneficiar!

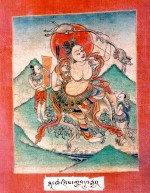

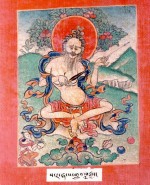

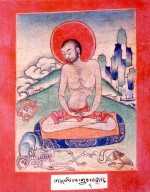

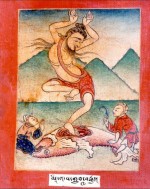

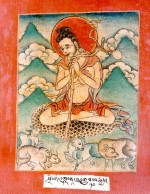

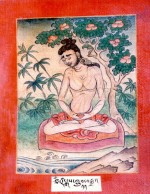

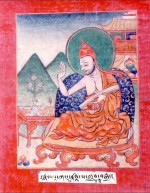

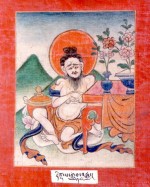

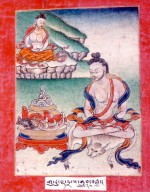

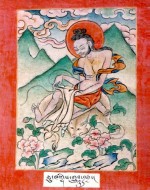

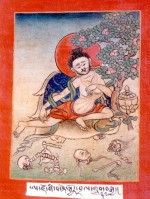

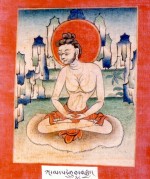

84 Mahasiddhas

Mahasiddhas – Who Has Attained Highest Level Accomplishment

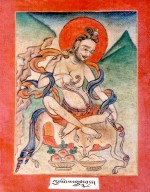

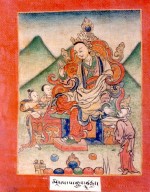

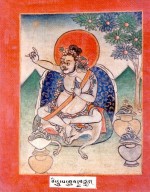

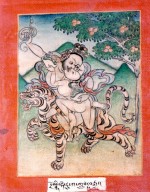

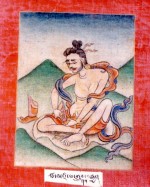

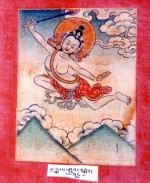

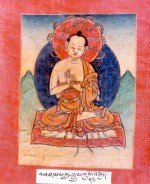

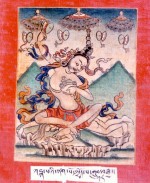

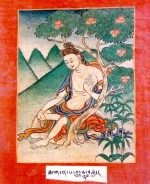

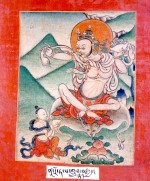

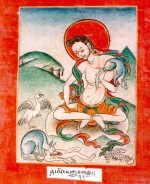

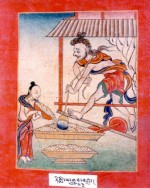

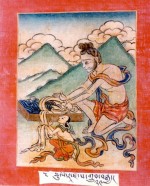

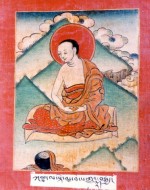

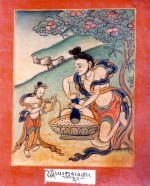

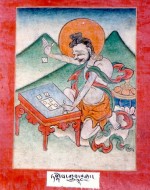

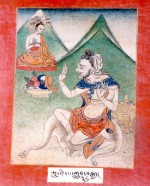

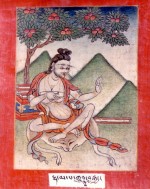

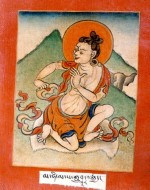

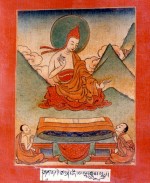

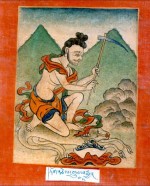

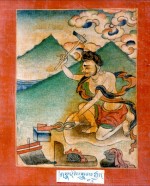

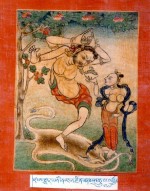

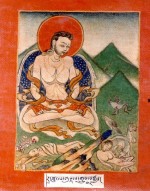

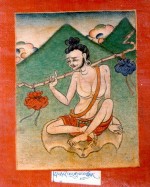

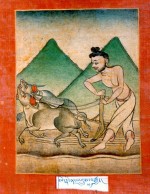

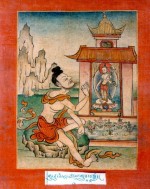

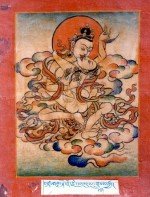

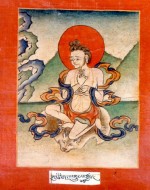

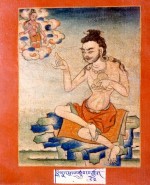

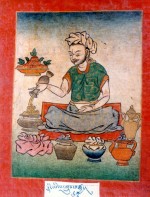

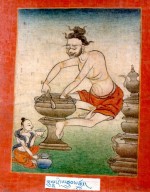

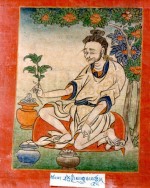

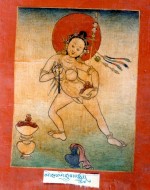

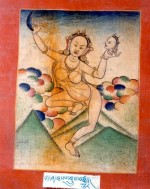

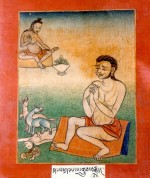

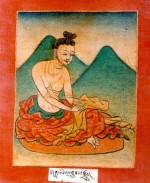

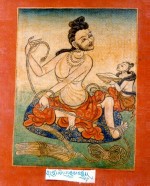

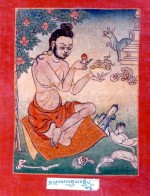

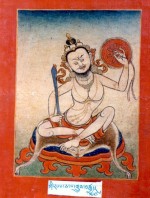

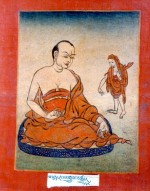

The Mahasiddhas, literally the ‘Greatly Attained Ones’, lived in India between the 8th and 12th centuries and were the instigators of the highly esoteric Yoga Tantra systems that were finally transmitted into Tibet. The Mahasiddhas came from all walks of life, and the diversity of their often-outlandish legends reveals much about the different approaches to enlightenment.

A practitioner who has attained the high level of realization of an Arhat is said to acquire at least six siddhis or powers. These powers include such seemingly miraculous abilities as the power to fly, to levitate, to make oneself invisible, to possess another person’s body, to decrease or increase one’s size at will, and to assume other forms at will. There are said to be 84 siddhis that one can attain through the ultimate realization of emptiness and the attainment of enlightenment. These 84 siddhis are exemplified in the popular stories of the 84 Mahasiddhas, each of whom represents one of the siddhis. These stories are very popular and well-known throughout Tibet and India as well as the other Buddhist countries of Asia.

One thing that stands out when reading the stories of the 84 Mahasiddhas is how different each of them are from the others. Some were kings, some monks, some itinerant ascetics, some fishermen and butchers. The one common thread throughout all the stories, however, is that these individuals all broke free of the limits and boundaries imposed on them by their circumstances and livelihoods. Monks, kings, householders, having accomplished the subtle practices of the highest tantric yogas, all abandoned their robes or their crowns or their families and wandered the mountains and charnel grounds free of attachment to anyone or anything. They often appeared as crazy hermits, unbound by any rules and living seemingly as they chose. Yet all remained true to their realization and their wish to liberate all beings from suffering.

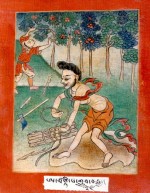

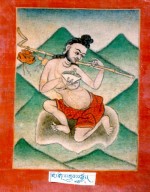

- Mahasiddha Luyipa Lūyipa / Luipa (nya’i rgyu ma za ba): “The Eater of Fish Intestines” ”The Fish-Gut Eater”

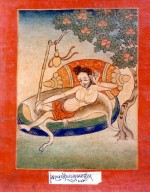

- Mahasiddha Lilapa Līlapa / Līlāpāda (sgeg pa): “He Who Loved the Dance of Life” ”The Royal Hedonist”

- Mahasiddha Virupa… Virūpa / Dharmapala (bi ru pa): “The Wicked” ”Master of Dakinis”

- Mahasiddha Dombhipa Dombipa / Dombipāda (dom bhi he ru ka): “He of the Washer Folk” ”The Tiger Rider”

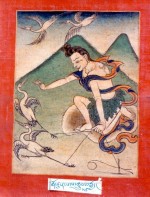

- Mahasiddha Shawaripa Savaripa / Shavaripa / Sabaripāda (ri khrod dbang phyug): “The Peacock Wing Wearer” ”The Hunter”

- Mahasiddha Saraha: The “Arrow Shooter”]”The Great Brahmin”

- Mahasiddha Kangkalipa Kankaripa / Kankālipāda (kanka ri pa): “The One Holding the Corpse” ”The Lovelorn Widower”

- Mahasiddha Menapa Mīnapa / Vajrapāda / Acinta (nya bo pa): “The One Swallowed by a Fish” ”The Avaricious Hermit” ”The Bengali Jonah”

- Mahasiddha Goraksa Goraksa (ba glang rdzi): “The Immortal Cowherd”

- Mahasiddha Sorangipa Courangipa: “The Limbless One”

- Mahasiddha Vinapa Vīnapa / Vīnapāda (pi vang pa): “The Lute Player” ”The Music Lover”

- Mahasiddha Santipa Sāntipa / Ratnākarasānti (a kar chin ta): “The Academic”

- Mahasiddha Tantipa Tantipa / Tantipāda (thags mkhan): “The Weaver” ”The Senile Weaver”

- Mahasiddha Tsamarepa Camaripa / Tsamaripa (lham mkhan): “The Leather-worker” ”The Divine Cobbler”

- Mahasiddha Khadgapa Khadgapa / Pargapa / Sadgapa (ral gri pa): “The Swordsman” ”The Master Thief”

- Mahasiddha Nagarjuna: “Philosopher and Alchemist”

- Mahasiddha Khanapa Kānhapa / Krsnācharya (nag po pa): “The Dark Master” ”The Dark-Skinned One”

- Mahasiddha Karnarepa Karnaripa / Āryadeva (‘phags pa lha): “The One-Eyed” ”The Lotus Born”

- Mahasiddha Thaganapa Thaganapa / Thagapa (rtag tu rdzun smra ba): “He Who Always Lies” ”Master of the Lie”

- Mahasiddha Naropa/Narotapa Naropa / Nādapāda (rtsa bshad pa): “He Who Was Killed by Pain” ”The Dauntless Disciple”

- Mahasiddha Shalipa Shalipa / Syalipa (spyan ki pa): “The Jackal Yogin”

- Mahasiddha Tilopa Tilopa / Prabhāsvara (snum pa / til bsrungs zhabs): “The Sesame Grinder” ”The Great Renunciate”

- Mahasiddha Saktrapa Catrapa / Chatrapāda (tsa tra pa): “The Beggar Who Carries the Book”

- Mahasiddha Bhadrapa Bhadrapa / Bhadrapāda (bzang po): “The Auspicious One” ”The Snob”

- Mahasiddha Dukhandhipa Khandipa / Dukhandi (gnyis gcig tu byed pa / rdo kha do): “He Who Makes Two into One”

- Mahasiddha Ajokipa Ajokipa / Āyogipāda (le lo can): “He Who Does Not Make Effort”

- Mahasiddha Kalapa Kalapa / Kadapāda (smyon pa): “The Madman” ”The Handsome Madman”

- Mahasiddha Dhubipa Dombipa / Dombipāda (dom bhi he ru ka): “He of the Washer Folk” ”The Tiger Rider”

- Mahasiddha Kankana Kankana / Kikipa (gdu bu can): “The Bracelet Wearer”

- Mahasiddha Kambala Kambala / Khambala (ba wa pa / lva ba pa): “The Yogin of the Black Blanket”

- Mahasiddha Bhendepa Bhandhepa / Bade / Batalipa (nor la ‘dzin pa): “He Who Holds the God of Weath”

- Mahasiddha Dhingipa Tengipa / Tinkapa (‘bras rdung ba): “The Rice Thresher”

- Mahasiddha Tantepa Tandhepa / Tandhi (cho lo pa): “The Dice Player” ”The Gambler”

- Mahasiddha Kukuripa Kukkuripa (ku ku ri pa): “The Dog Lover”

- Mahasiddha Kuzepa Kucipa / Kujiba (ltag lba can): “The Man with a Neck Tumor”

- Mahasiddha Dhamapa Dharmapa – (tos pa can): “The Man of Dharma”

- Mahasiddha Mahalapa Mahipa / Makipa (ngar rgyal can): “The Braggart”

- Mahasiddha Acinta Acinta / Atsinta (bsam mi khyab pa / dran med pa): “He Who is Beyond Thought”

- Mahasiddha Babehepa Babhahi / Bapabhati (ch las ‘o mo len): “The Man Who Gets Milk from Water”

- asiddha Shantideva Bhusuku / Shantideva (zhi lha / sa’i snying po): ”The Lazy Monk”

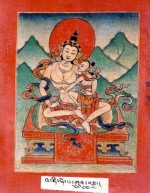

- Mahasiddha Indrabuti Indrabhūti / Indrabodhi (dbang po’i blo): “He Whose Majesty Is Like Indra” ”The Enlightened King”

- Mahasiddha Mekopa Mekopa / Meghapāda (me go pa): “The Wild-Eyed Guru”

- Mahasiddha Toktsepa Kotali / Kotalipa / Togcepa (tog rtse pa / stae re ‘dzin): “The Ploughman” ”The Peasant Guru”

- Mahasiddha Kamparipa Kamparipa / Kamari (ngar pa): “The Blacksmith”

- Mahasiddha Zaledarapa Jālandhari / Dzalandara (dra ba ‘dzin pa): “The Man Who Holds a Net” ”The Chosen One”

- Mahasiddha Rahulagupta Rāhula (sgra gcan ‘dzin): “He Who Has Grasped Rahu”

- Mahasiddha Dharmapa Dharmapa (thos pa’i shes rab bya ba): “The Man of Dharma”

- Mahasiddha Dhokaripa Dhokaripa / Tukkari (rdo ka ri): “The Man Who Carries a Pot”

- Mahasiddha Medhenapa Medhina / Medhini (thang lo pa): “The Man of the Field”

- Mahasiddha Sankazapa Pankaja / Sankaja (‘dam skyes): “The Lotus-Born Brahmin”

- Mahasiddha Gandrapa Ghandhapa / Vajraganta / Ghantapa (rdo rje dril bu pa): “The Man with the Bell and Dorje” ”The Celibate Monk”

- Mahasiddha Zoghipa Yogipa / Jogipa (dzo gi pa): “The Candali Pilgrim

- Mahasiddha Tsalukipa Caluki/Culiki: “The Revitalized Drone”

- Mahasiddha Gorurapa Godhuripa / Gorura / Vajura (bya ba): “The Bird Man” ”The Bird Catcher”

- Mahasiddha Lutsekapa Lucika / Luncaka (lu tsi ka pa): “The Man Who Stood Up After Sitting”

- Mahasiddha Nalinapa Nalina / Nili / Nali (pad ma’i rtsa ba): “The Lotus-Root”

- Mahasiddha Nigunapa Niguna / Nirgunapa (yon tan med pa): “The Man without Qualities” ”The Enlightened Moron

- Mahasiddha Nandhipa Jayananda: “The Crow Master”

- Mahasiddha Patsaripa Pacari / Pacaripa (‘khur ba ‘tsong ba): “The Pastry-Seller”

- Mahasiddha Tsampakapa Campaka / Tsampala (tsam pa ka): “The Flower King”

- Mahasiddha Bhichanapa Bhiksanapa / Bhekhepa (so gnyis pa): “The Man with Two-Teeth” ”Siddha Two-Teeth

- Mahasiddha Dhelipa Telopa / Dhilipa (mar nag ‘tshong mkhan): “The Seller of Black Butter” ”The Epicure”

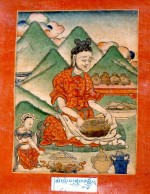

- Mahasiddha Kumbharipa Kamparipa/Kamari: “The Potter”

- Mahasiddha Sarwatripa Caparipa

- Mahasiddha Manibhadra: “She of the Broken Pot” ”The Model Wife”

- Mahasiddha Mekhala: “The Elder Severed-Headed Sister”

- Mahasiddha Kanakhala: “The Younger Severed-Headed Sister”

- Mahasiddha Kalakala Kilakipala: “The Exiled Loud-Mouth”

- Mahasiddha Kantalipa Kantali: “The Tailor” ”The Rag Picker”

- Mahasiddha Dhahulipa Dhahuli / Dekara (rtsva thag can):“The Man of the Grass Rope”

- Mahasiddha Kapalapa Kaphalapa / Kapalipa (thod pa can): “The Skull Bearer”

- Mahasiddha Udhelipa Udhilipa: “The Flying Siddha”

- Mahasiddha Kiralawapa Kirava/Kilapa (rnam rtog spang ba): “He Who Abandons Conceptions” ”The Repentant Conqueror”

- Mahasiddha Sakarapa Saroruha / Sakara / Pukara / Padmavajra (mtsho skyes): “The Lake-Born” ”The Lotus Child”

- Mahasiddha Sarwabaksa… Sarvabhaksa (thams cad za ba): “He Who Eats Everything”/”The Empty Bellied Siddha”

- Mahasiddha Nagabhodhi Nāgabodhi (klu’i byang chub): “The Red Horned Thief

- Mahasiddha Dharikapa Dārika / Darikapa (smad ‘tshong can): “Slave-King of the Temple Whore”

- Mahasiddha Putalipa

- Mahasiddha Sahanapa Panaha

- Mahasiddha Kokilapa Kokalipa / Kokilipa / Kokali (ko la la’i skad du chags): “The One Distracted by a Cuckoo”

- Mahasiddha Anangapa Ananga / Anangapa (ana ngi):“The Handsome Fool”

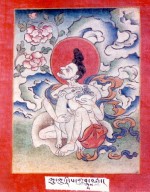

- Mahasiddha Lakshimikara Laksminkara: “She Who Makes Fortune” ”The Mad Princess”

- Mahasiddha Samudra: “The Beach-comber”

- Mahasiddha Vyalipa: “The Courtesan’s Alchemist”

This document is free for download and personal use. They are not to be published commercially. All rights reserved.

Cintamani - Meditação e Arte - Copyright 2020 - Todos os direitos reservados.

Cintamani - Meditação e Arte - Copyright 2020 - Todos os direitos reservados.